An Ode to Amateurs

Or, What the Erie Canal Teaches Us About Progress

The only way to understand me is as a Philadelphian. Although I have not lived in Pennsylvania for over a decade – nor did I spend more than four years living in the city proper – I am through and through a Philadelphian. This explains many things about me such as my love of Rocky or my love of roast pork sandwiches. But primarily, it influences my obsession with the rise and fall of cities.1

There was a time when Philadelphia was considered the Paris of the West. In the early days of the Republic, there were no cities more important. We founded the nation. We were both the financial and political capital of the country. We were on track to be the London of America. And that is not the Philadelphia that existed by the time I was born. With the exception of a Merv, the reason a city rises or falls is always complex. Philadelphia is no different, with many reasons from the incompetence of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania leads to outside forces like Alexander Hamilton and Andrew Jackson. But there’s one that annoys me above all others: the Erie Canal.

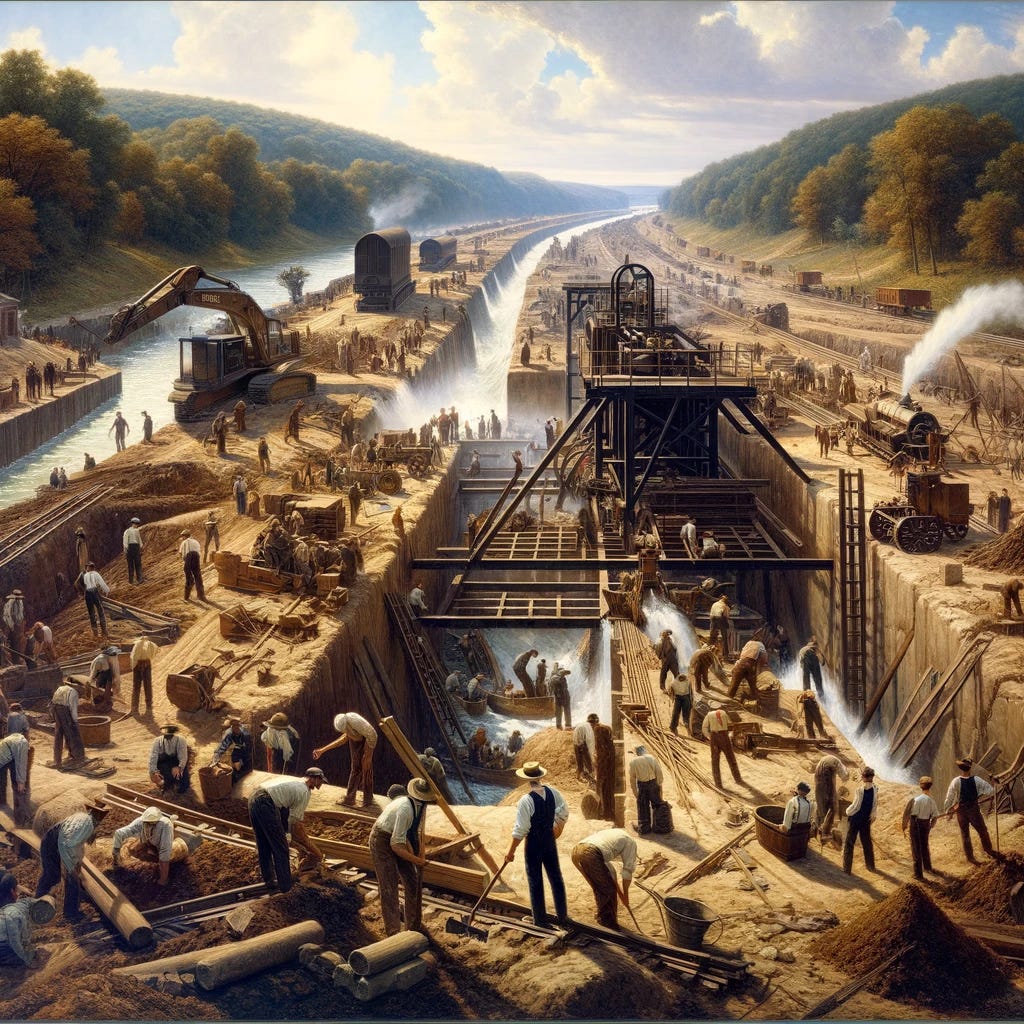

The short version is that the Erie Canal connected the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, creating a continuous water route from the Atlantic Ocean to the interior of the country. In the days where moving things by water was significantly easier and cheaper than by land, this was monumental. New York City become the harbor and the hub of trade. Which led to a population increase and an increase in prestige and all the other commensurate benefits such as becoming the commercial capital of America. And eventually, the world. You have a good run, City of Brotherly Love, but good night, sweet prince.

There are a lot of lessons we can learn from this. One of which is the importance of natural features. One of the curses of the Age of Enlightenment is we often feel as if we are above such natural factors influencing our life, even though much of human history is the history of geography. Building the Canal was always going to be easier for New York than Pennsylvania.

Another potential lesson is that the best technology doesn’t always win. The Main Line of Public Works – Pennsylvania’s version of the Erie Canal – was an engineering marvel. Using both canals and railroads it managed to connect Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Yet, despite being more technically impressive, it was less efficient and more costly, and in the long run, it lost.

Another potential lesson is the value of vision.2 New York’s greatest Clinton, DeWitt – and I know that may be controversial but George did grow up in New Jersey – was a strong and visionary leader who fought for the Canal while Pennsylvania’s leaders dithered.

But the lesson I want to discuss is about the Erie Canal itself. The value of amateurs.

As Governor of New York, and a member of the Erie Canal Commission, DeWitt Clinton is perhaps the man most responsible for the Erie Canal. And do you know what he was not? An engineer. He was essentially a lifelong politician. But he had a vision, one many at the time thought was impractical. But that did not stop him. Most of the work on the Erie Canal was done by amateurs. There were not enough trained engineers to handle the project, but that did not stop them.

This is, of course, not unusual. For the entirety of human history, humans could not fly. Balloons allowed for the ability sort of fly, but that was it. Then along came the Wright Brothers. Unsurprisingly, they did not hold doctoral degrees from a prestigious school in aeronautical design because no such thing existed. They didn’t even have diplomas. They were not trained engineers. They were smart and they were visionaries, and they spearheaded one of the greatest advances in human history.

These types of stories are not unusual. Gregor Mendel practically invented the science of genetics. Was he an Ivy League educated scientist? No, he was a monk. Michael Faraday was self-educated. Many great innovations come from amateurs.

And this has some very good reasons. The first is that for many fields, it would be difficult to have anyone who wasn’t an amateur until the field is created. But there’s a less practical and better reason: imagination.

We lawyers are a risk averse profession. In fact, that’s a sign of being a good lawyer. We assess risk and we lead our clients away from it. And in a profession built on following rules and precedent, this makes sense. The most intellectually rewarding work in my career has been when I pushed the boundaries. Having a judge tell you that you’ve made a novel argument and they find it compelling is a great feeling, quickly overpowered when they follow that by telling you that you lost. Because of precedent. Lawyers are specialists who operate inside of tightly constructed boxes and help other people do the same.

Unfortunately, the lawyer approach also spreads to almost all other professions. As a profession grows, it becomes more specialized and more constrained. Innovative thinking is discouraged. And for many fields that is fine. But for the fields that we rely on to push humanity forward, it is a real bummer.

One of the common things you’ll hear about Steve Jobs is that he wasn’t a real engineer. And to a great degree, that explains his brilliance as a visionary. But that doesn’t mean real engineers can’t be visionaries. No one is going to say Mark Zuckerberg couldn’t code. The problem that real engineers have is the same problem that real lawyers and real doctors and real librarians and real football coaches all have: you get to that place by knowing what cannot be done. But while those norms, conventions, and preconceived notions are our greatest strength, they also weigh down upon our ability to look beyond that. To see fresh perspectives.

If you research the question of why amateurs have increasingly disappeared from technological progress, you will often see specialization raised as a reason. Look guys, things are just so much more complex now. The Wright Brothers wouldn’t know how to build a Boeing 737 MAX. Things are just too complex now, you need such specialized knowledge to do anything that amateurs just can’t play.

My gut tells me this argument is part true and part nonsense crafted by people who spent a lifetime educating and working in a specialized field to make themselves feel better.3 More importantly, this limits one of the great elements of creativity.

One of the more insulting compliments I ever received was when a young lady – whom I happened to be quite fond of – was genuinely shocked that a song I wrote was good. The reason as she explained is that in her mind, creativity – particularly musical creativity – was associated with the type of guys that she, frankly, preferred to me. The scruffy guitarist who sits around smoking weed, not the well-groomed lawyer who plays music on the side. This is a common way of thinking. People think of creativity as being somehow divorced from the brain, from analytical and logical thinking abilities. If you’re good at the latter two, you must not be good at the former. Creativity comes from muses, who are scared off by too much book learning.

But all history tells us the opposite is true. Creativity is a complex thing but it’s largely driven by the ability to connect disparate ideas in novel ways. We know that the part of the brain that is associated with our executive functions is highly connected to creativity. It’s the Don Drapers of the world who are creative, not the people who sit around trying to look creative.

The upshot of this is that great advances come from smart people connecting ideas across various areas. We’re familiar with the obvious examples, such as the aforementioned Steve Jobs or the greats like Leonardo da Vinci and Thomas Edison. But there’s someone more alive who demonstrates the value of standing at the intersection of art and science: James Dyson.

I have always wanted one of this man’s vacuum cleaners, so I am biased. But I find his story interesting. Vacuum cleaners had existed for over a century, they were a specialized technology. Along comes this guy who is frustrated with his vacuum, and he revolutionizes the entire field. Dyson did have experience with engineering, his education was in industrial design and he had prior inventions. But you know what he was not? A guy who designed vacuum cleaners for a living. If he had been, he never would have been able to come up with the idea of a vacuum without a bag.

The other interesting part of his story is that before he began studying engineering, he studied art. One of the great tragedies of modern schooling is that it tries its darndest to build a wall between art and science, even though that intersection is where magic happens.

When I used to teach test prep, one of my favorite things to do would be to ask LSAT students – almost exclusively from the arts and humanities and social “sciences” – a question even remotely related to science. Their inability to answer was matched only by asking MCAT students – almost exclusively from the sciences – to name their favorite book. There’s a good chance that the more artistically inclined of you reading this think of engineers as uncultured barbarians while the engineers reading this think of you as frivolous fools. This is to society’s detriment. The way liberal arts has become a punchline is to society’s detriment. The classic liberal arts education was in both art and science. And that was good, because each compliments and improves the other.

Instead, we’ve created a world where specialization – and worse, credentialism – is prioritized. And because we increasingly design our world around the idea that the decisions you may at 17 are the ones that dictate the course of your life, we are increasingly closing the doors on people bringing the type of diverse educational or work experiences together that are so helpful to the proliferation of new ideas.

But ironically, this will increase the importance of amateurs. Will we be likely to hire a bunch of people with no training to build an engineering marvel? No. Nor do I think what we really need is for Alphabet or OpenAI or whomever to fire half their staff and replace them with random people on the street. But honestly that may be a better approach than walling off technology and engineering from the masses.

Perhaps the most exciting company today is SpaceX. They are a company founded explicitly on the vision of making humanity multiplanetary. This idea is absurd, as I’ve already written. But they’re genuinely doing exciting things. And they are a company run by an amateur.

We will always need DeWitt Clintons. We need people who don’t know what they’re doing, but can see things others can’t or won’t see. It’s how progress is made.

This is a lie, it primarily influences me in my love of the Eagles and being somewhat casually rude without realizing it.

Originally, this was a two-parter, with the second being the importance of vision, this one focusing on why amateurs often provide so much vision. But I’ve learned that if I title an article in such a way it seems like a series, the views for it drop massively. So you will not see any more series here, but I may try and backdoor them in like this!

It certainly makes me feel better as someone who spent a lifetime educating and working in a specialized field.

I like this. Maybe the reason for the decline in amateurism has more to do with cultural expectations (homogeneity and lack of a ‘scene’) than it does complexity.

It is an act of stubborn individuality to pursue something as an amateur, and this perspective helps me recommit.

This is a wonderful essay and brings to mind so many things..like the development of cities on the Ohio River.

I am always saying to people who complain abt traffic and winding streets in town that the reason for the roads being the way they are is the river--often they say, "what river?" Isay, "the rover that means you have to cross it on a bridge"--since the bridges are often flat they don't know abt the river.

My minor in grad. school was history of technology.