Attack of the Drones

The looming threat even more dangerous than Episode II's Crappiness

I try and follow three basic rules of writing. The first is know your audience. The second is never use complex language when simple language will do. And the third is to always have a clear thesis. I break all of them from time to time but that last one is the real bear. These articles are normally the result of many head clearing walks with my dog as I ponder what I really want to say. Thankfully, he loves walks. Which, incidentally, means supporting this newsletter makes this pup a happy boy so make sure you like, share, and subscribe.

But no matter how many walks that little guy got while I worked on this one, I could not come up with a good thesis. I’m telling you up front that all I got on this one is that I think there is a looming potential problem that not enough people are talking about. And we should be talking about this a lot more because the potential consequences are severe. And that looming problem is that I believe drones can end civilization.

There’s this distasteful social media style of speaking where everything is catastrophized and one of its manifestations is this quasi-eschatological belief that somehow being alive in [insert year here] is the worst. Many of these people have never read history. We’ve made so many advances in making people safer, freer, and more prosperous that it’s mindboggling. One of those great advances is that political violence – particularly assassination – has become much less common, particularly over the last half century. The last time we had an American President shot was before I was born (barely). Even the high-profile attempts on Bill Clinton were almost thirty years ago. Assassinations seem like a relic that belongs in a distant past, the province of anarchists and the IRA, not part of the modern world. Thus, when they come back into the news, they’re shocking and horrifying events. And that’s good because assassinations are bad.

I’d love it if everyone took that as a given, but in case you’re one of those people that likes evidence, I’m not sure I can give you satisfying evidence. The science on the effects of assassination is spotty. Some claim assassinations have become more common, less common, are consequential, are inconsequential, and pretty much any combination. You can find data saying they’re actually good things and promote democracy! You can look at them as being very influential. I was unimpressed by every study I saw – although I linked to the two that most disagree with me – and I feel like we have to eyeball this one.

Leaving aside the most committed pacifists, we can probably agree that not every assassination is bad. Many wish one of the numerous attempted assassinations of Adolf Hitler had worked, and I think if time travel worked this way we’d have a successful crowdfunding to hire Carlos the Jackal to go back and do the job right.1 But other than the most extreme cases, assassination is inherently bad. For all its many flaws over the millennia, the great innovation of government is that giving the state a monopoly on violence is a better alternative to everyone freely wielding it on their own. Assassinations are a throwback to that, and government can’t last. Of the 69 Roman Emperors – before its split into two – 34 were assassinated.2 Power lies not in the hands of the government – which in a democracy we like to believe is the people – but in the hands of whomever wields the blade. I don’t need a social scientist to tell me if that’s good or bad.

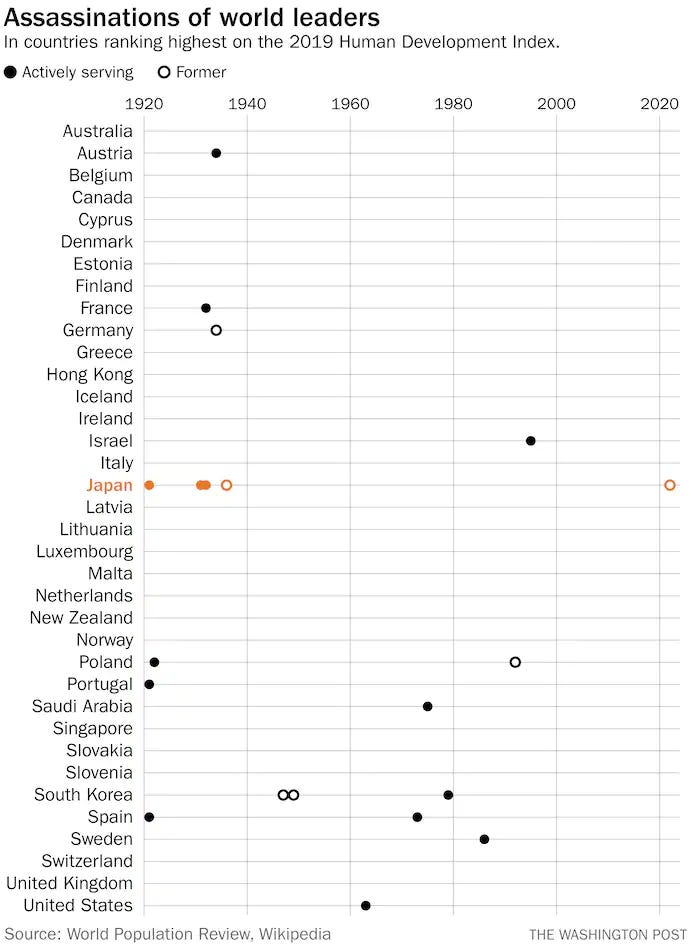

So now that I’ve hopefully convinced you that assassination is bad, let’s talk about why it’s rare. But to do that we need to delineate the two types of assassinations. The first is when one country’s government assassinates someone of another country. These are a form of war. The other type is what we commonly think of, when someone in their own country assassinates a political leader. As this chart I stole from the Washington Post shows, we’re a far way from Rome:

That chart should raise the question of why assassination is relatively rare. Think about all the political rancor. Just look at America alone. When I was a kid, I remember being told Bill Clinton was going to put people into FEMA concentration camps. When I was a little older, a lot of people called George W. Bush the new Hitler. When I was a little older than that, a lot of people called Barack Obama a Muslim Hitler. When I was even older, a lot of people called Donald Trump a new Hitler. And yet, two things are true. One, people desperately need a new reference other than Hitler.3 And two, there were never serious assassination attempts on any of these people. Why?

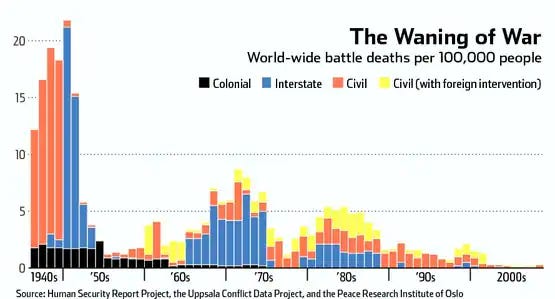

Of course, it’s impossible to study this but we can apply some logic. The first is that state against state assassination can spark war. Even though it didn’t involve a direct agent of a state, it’s easy to find a good example of how disastrous this can turn out.4 Even America – from the follies of the CIA to the more popular “targeted killings” of the War on Terror that continue even today – limits itself to countries that pose no threat. Unless you’re a superpower or under the protection of a superpower, it’s too risky. To simplify a very complex problem, part of why there’s so much less war is that the stakes just got too high.

But that doesn’t explain the domestic variety. I think the reason for that is obvious: it’s difficult to do. We don’t have a lot of data points here, but we know that the first three presidential assassinations all had the same method: walk up to the President and shoot him. That’s not possible anymore. And for as much as I praise 19th century innovation, it’s staggering that it took three times before realizing there should be countermeasures to “walk up to the President and shoot him” as a method of assassination. Thankfully, we do better now. In the criminally underrated 1993 film In the Line of Fire,5 John Malkovich’s character states that all it takes to kill the President is to be smart and willing to trade your life for his. That’s a great scene but it’s not true. With all due respect to the great Michael Corleone, not everyone can be killed.

Of course, there are politicians of the non-world leader variety. Unfortunately, they’re not as protected. In the last few years, we’ve tragically seen two British MPs murdered and the horrific shootings of Gabby Giffords and Steve Scalise. As terrible as those are, they also drive home how rare this is. Prior to the Giffords shooting, dating back to the end of Reconstruction there were only five incidents of members of Congress being targeted. Two of those were running for President and one was murdered at the direction of Jim Jones. Jo Cox was the first MP murdered by someone other than an Irish nationalist since 1812.6 So even these types of assassinations are rare. But why would that be?

Again, it’s impossible to prove this, but I think there’s an answer in what we saw with members of Congress. It’s just not that impactful to the operation of government. Killing Huey Long or Bobby Kennedy potentially altered history. Killing your local state representative won’t. And to the type of diseased mind that would consider an assassination, presumably the size of its impact is important. If you’re going to trade your life, you want to win the trade. And the bigger that trade, the more impossible it gets, which winnows down the type of people who would take that chance. This is how you end up getting so many ludicrous, easily foiled plans like flying a plane into the White House or flipping the President’s limo with a forklift. It’s a sinister calculus, but somehow, it works because these remain rare.

But what if that calculus changed? What if it became easier to kill than it did to stop a killer? And what if it became easier to kill without getting caught?

Well, that’s worrisome. And what’s worrisome isn’t that this robot dog is going to start wreaking havoc next week. It’s that it was so cheapy and easy to make. This isn’t the stuff being built by military contractors, this is what a rando can build. What’s the next iteration? And the next iteration? If you want something more professional, how about a grenade launcher that can shoot drones?

I’d recommend reading this entire article, but because it’s long, here’s a taste of it:

These diminutive quad-copter-type drones can be fitted with various payloads, ranging from full-motion electro-optical video cameras to small high-explosive or armor-piercing warheads, and that can fly together as a swarm after launch.

What does that mean?

What this means is that a single individual could fire multiple Drone40s with kinetic payloads and then they could be directed to fly to a designated point, after which they would all drop at the same time.

We’re still in the opening stages of this technology and it’s already devastatingly lethal. And because that calculus I talked about earlier is so imprecise it’s impossible to know how much those variables must change for a nightmare scenario to unfold. How much more covert do killings need to become before more actors – state or individual – will embrace them? How much easier do they need to become for less protected potential targets to become targets? How far away are we from technology that could change the calculus enough that even world leaders would no longer be safe? And what does a world with that much political violence look like? How long does democratic, civil society endure under those circumstances? What does a version of the Patriot Act written by people trying to save their own lives look like?

Any technology we invent is going to be used for killing. Earlier (in a footnote if you don’t read those) I said it’d be better if people were more familiar with WWI than WWII and made those references. Part of the horrors of the Great War was that those 19th Century technological advances I frequently extoll were used for killing. Just think about the name: the machine gun. As my favorite professor would say, World War I was when the French Revolution met the Industrial Revolution. What happens when that meets the Digital Revolution? Forget cyber warfare or the dangers of AI, what about covert robotic warfare?

I’m trying very carefully to not get too deep into the weeds here about how this could work. And although that means we’re a little light on the tech talk, it also means my Substack isn’t sketching out methods of assassination, because I’d like to avoid that. But we have imaginations, so I don’t think I need to spell it out. If you think Oswald was a patsy,7 you can imagine the immense value of a patsy that can literally be programmed.

Of course, as I keep noting, it’s unlikely we’re there yet. It’s also true that there are ways to counter drones – particularly the airborne kind – and more will likely be created. The very absence of robots in daily life works against them. Assassins can blend in with the crowd. A robotic dog can’t. And of course, drones have a lot of value to give society other than just killing. We’re not going to solve this potential problem by outlawing robotics, nor should we. But this brings me back to where we started: I have no good thesis here. I can’t tell you what the impact of our robotic friends being turned into killing machines will have on the world. And I have no solutions either. What I do know is that changes to any ecosystem can have unanticipated effects. And without anyone intending to do so, we’ve potentially shifted the balance from defense to offense in a way that could have drastic consequences. It’s important, and we should talk about it more.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I need to go walk my dog and think about whether a gig economy can last in a world built for factories, as we’ll discuss next time on Technopoptimism.

This is the second week in a row I’ve pitched a great movie idea. If someone who hasn’t recently written a piece highly critical of Netflix can get me a production deal, I’d really appreciate it.

The Eastern Roman Empire – or as it’s anachronistically known, Byzantine Empire, was somehow worse. Of the 107 Eastern Roman Emperors, 65 were assassinated.

The irony that I referenced him earlier is not lost on me. But that one was germane to the discussion!

As a follow up to my previous footnote, I believe we’d live in a better world if people were more familiar with WWI than its sequel and made the references to match.

Seriously people, it’s on Netflix. Get to streaming.

That was the murder of Spencer Perceval, the only Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (Hi British and Northern Irish readers!) to ever be assassinated. For my American readers, I recommend that you read about this – once you’re done hitting the like button here and commenting, of course. It outclasses the Garfield Assassination in sheer bizarreness.

I really wanted to use this footnote to lay out all my thoughts on the JFK Assassination, but this article is already longer than usual. I am willing to be swayed by arguments so let’s see if we can solve the whole thing in my comments section.

I appreciate your comment and footnote about knowing WWI history better. I read “All Quiet on the Western Front” for the first time (along with my kid’s 10th grade English class last year) and then watched the movie after, and I was completely gutted. Horrors upon horrors. We tend to think of the Nazis and Hitler’s rise to power as an historical aberration. He didn’t appear out of nowhere. Context is everything people! I recommend listening to Dan Carlin’s “Hardcore History” on WWI, great way to step back in time and revisit the Wehrmacht before it was corrupted by the Nazi party. A telling lesson for us today.

Every technological advancement is going to be used for killing people and then refined until it's better at killing more precisely or indiscriminately. Which isn't great!

Robotic assassinations are something I hadn't considered before, but someone's going to figure out how to do this and upload the plans to the internet so that any freak with enough time, determination, and instability will be able to make their own little robot killing machine.

I'll have to do some thinking here.