Binge and Praise

Or, How I Was Wrong About Netflix

Once upon a time, I had an idea about Netflix. And I began writing an article about it. But before I finished, I stopped publishing this newsletter. But I couldn’t forget that article. I kept working on it and eventually I relaunched this newsletter with it, and it did okay, a few dozen people read it. Then that jumped up to a few hundred. Then it kept going and going and is still – by far – the most widely written thing I have ever written. And in it I was wrong.

My cousin Tommy knew more about business and the stock market than anyone I knew, but he was wrong big on Amazon, a company he never believed in. But his reason for being wrong was good: he could not imagine a world where a company could lose money for almost a decade and survive. His assumption was wrong, not his application of it. He wasn’t ready for the new world of tech companies not needing to do the basic survival tool of business: make money.

Similarly, I made an assumption about Netflix, which is that a content distributor/creator that does a poor job of distributing and creating content is not going to win in the long term. But boy are they winning big now.

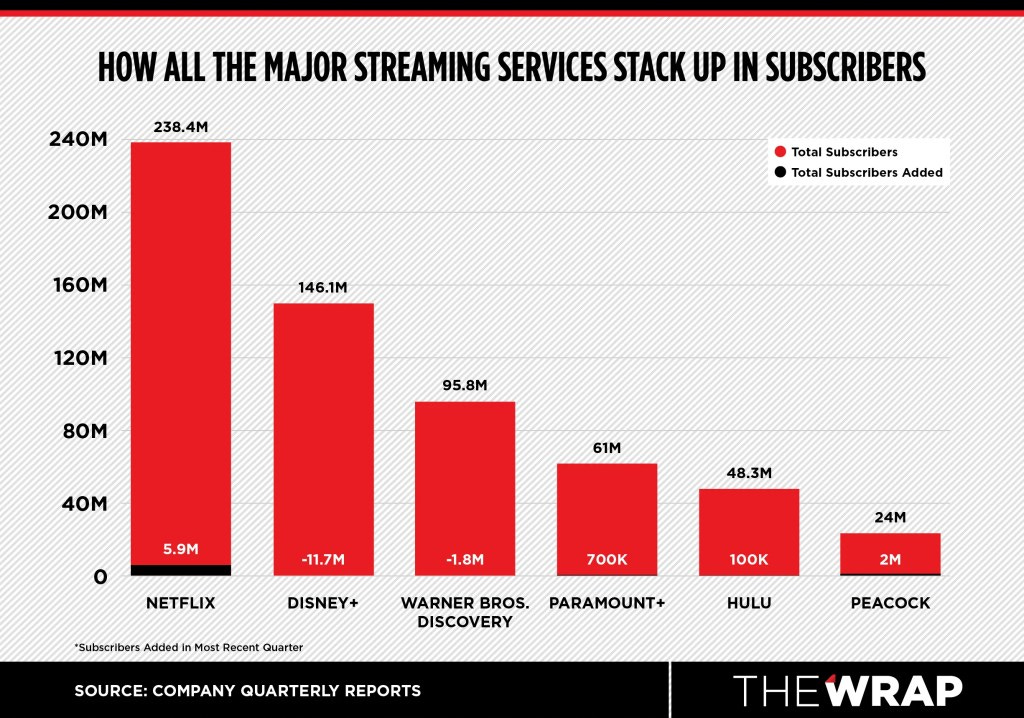

Netflix is making money, and their competitors are losing it in buckets. In 2023 the Netflix competitors – Disney, Warner Brothers Discovery, Comcast, and Paramount – lost a combined FIVE BILLION DOLLARS competing with Netflix. So why is this little tech company mercilessly beating their non-tech counterparts?

My criticism of the Netflix model mainly lied in their departure from timeless models for distributing content in a way that works to build popularity. I maintain that this was, and still is, correct. But my other assumption was that their competitors would not choose to do something even more baffling. They chose to depart from the core strategy of any business.

Essentially, there’s a few timeless truths about television and movies – and art and entertainment in general – that the non-Netflix streaming services abandoned. And the first one requires me to – more than at any time other than my early work – wade perilously close to the waters of the culture war. Because it’s difficult to discuss the decline in quality on streaming services without touching on what I like to call the Left Behinding of media.

For those of you unfamiliar with Left Behind, it is a series of fantasy novels exploring the aftermath of the Rapture. It is a 20th Century work that is fundamentally and consciously Christian. It sold an immense number of copies and was eventually turned into a series of films that were incredibly successful, almost universally beloved, and won numerous Academy Awards. Oh, wait, I got confused and started talking about The Lord of the Rings. Every word I wrote after “Rapture” applies to the most famous fantasy novel of all time. There is perhaps no greater work of Christian – specifically Catholic – work of art of the last few centuries. But whereas Left Behind was read and watched primarily by fundamentalist Born Again Christians (or people hate watching it) the latter became so popular that there will be endless people claiming it isn’t Christian art, ignoring Tolkien’s own words. And the reason for this is, to again leave it to Tolkien’s words, that he understood that making Christianity explicit would be, to use his word, fatal.1[1]

For all but the most exceptional creations, being explicit about your themes kills the audience’s enjoyment, thus killing your work. Creating great art – or entertainment – is such a challenge that making it more difficult for yourself is usually avoided. It is possible to make a work of art that is explicit in its themes – whether they be religious or political – and have it be great. But Bertolt Brecht is not walking through that door. And so long as Hollywood continues to desire making modern Left Behinds, it will continue to dwindle its audience to only those who both agree with the message and don’t care about quality.

Politics done. And although this is a serious problem, it’s one that is symptomatic of the much bigger problem the non-Netflix streaming companies have. But before we identify that problem, let’s look at what Netflix does right.

If you were to ask what Netflix’s biggest success stories are, you will typically get answers such as House of Cards, Orange is the New Black, Stranger Things, or Squid Game. But the real answer is The Office, Friends, and Suits. Article after article has been written trying to explicate why so many people used to skip past the expensive new content to rewatch The Office for the umpteenth time. Or why Friends became an iconic show for people too young to have watched it originally. Or why Suits became the show of 2023. Which I don’t get because their success is somewhat obvious.

Let’s begin with Suits. I’ve stated before that the worst thing creatively about the Netflix model is the rise of the concept of the thirteen-hour movie. You know why actual movies aren’t thirteen hours? Because they would suck. A movie needs to be a self-contained, satisfying experience. Peter Jackson adapted the aforementioned Lord of the Rings into a trilogy which, if you sit and watch all three special editions,2 is twelve hours. But each movie is a self-contained story that is enjoyable on its own.

Television has historically strived to achieve that, first through the episodic model, then through the serialized model. Due to many reasons including financial and technological, television dramas moved from a 22–26-episode season down to 13. This helped spark the Peak TV phenomena of prestige dramas. But as highly serialized as those shows were, they still embraced episodic storytelling, which is where television shines. For example, the two highest rated Sopranos episodes on IMDB are “Pine Barrens” and “Long Term Parking,” each of which are contained, satisfying stories that are enriched by the serialization (spoilers in the footnote)3. As binge-watching became the norm, and television seasons shrank even lower than 13, the “television as a long movie” theory became dominant, resulting in shows not enriched by serialization but dependent on it. It also resulted in dwindling audiences and a general sense of declining quality.

Because it was not created to be a prestige drama, Suits was not made to be a series of 13-hour movies. It was made to be an enjoyable, forty-some minute experience. Yes, there are elements of serialization, even dramas in the 80s and 90s had that. But to enrich, not as the sole purpose. Zoomers learned they could put on a procedural legal drama, enjoy an episode or two, and go about their lives. Procedurals particularly and episodic drama in general are playing on easy mode. And streaming services treat making new series on that model as if you were asking them to make hardcore pornography. It’s telling that Disney has spent an unfathomable amount of money, used state of the art special effects, and a veritable who’s who of great actors to bring Marvel superheroes to television. Their reward has been a destruction of what was a few years ago the most valuable brand in America behind the NFL. Audiences have become so small that Disney+ even embraced their once scorned binge-watching model. The only thing they won’t do is try and make a show similar to the most successful and iconic Marvel television show ever:

But even more despised is the veritable snuff film that is a 23-episode comedy. I’m certain that if you even pitched one to Disney+ they would have you arrested. Meanwhile, people keep rewatching The Office and Friends. Why?

Last year I watched the new Frasier series on Paramount+. Although not as good as the original – almost no shows have ever been – I found myself enjoying it. As the season went on, I liked it more, becoming charmed by the characters that originally seemed little more than cardboard cutouts. I was becoming a genuine fan of this show. And then after 10 episodes it just… ended. That’s it, see you…. Someday? This of course led me to watch all 22 seasons of Cheers and Frasier. And the failure of modern sitcoms was obvious.

Televised comedy relies on four elements. The first two – jokes and plots – are, like movies, often standalone. They’re funny or they’re not. The latter two – characters and world – are, unlike movies, enriched by the television experience. The sheer time spent with a show creates deep audience connection. When Lucy had a baby, she had spent fifty episodes in the homes of Americans. They cared. If you ever wonder why sitcoms almost always get better, it’s both because it takes time for the writers to find the character’s voices, and because you care more about the character and the world they inhabit as the show goes on. I often embed videos just for a joke or to break up the flow, but I encourage watching this video of great Seinfeld moments because it’s a perfect illustration. Some of these jokes are independently funny, the humor deriving from much of what Jerry’s stand-up did, commenting on the world and its annoyances. But almost all these jokes are improved by your knowledge of the characters, and some are dependent on it. Jerry and Kramer acting like each other is hilarious, if you’re on your 127th episode of knowing these characters. Otherwise, perhaps mildly amusing? That holds for all of these bits. The jokes and plots make them funny. The characters and the world of Seinfeld make them classic.

Shorter seasons provide possible benefits to dramas – in terms of plotting at the cost of character development – but are almost entirely negative for comedies. The possibly apocryphal quote attributed to Stalin that quantity has a quality of its own does not just apply to armies but also to sitcoms. The sheer volume of episodes churned out by The Office and Friends contributes to how beloved they are. Viewers know and care about these characters and their world. They want to visit Dunder Mifflin’s offices or drop by Central Perk. Despair about this all you want, but sitcoms served an important purpose in American life. As our real community declined, a fake community grew. The creators of Cheers once said they created a neighborhood bar for everyone who didn’t have a neighborhood bar. And it worked. There’s a reason that 93 million people went to the place where everybody knew their name. Can you make a quality sitcom with few episodes? Sure, if you have creators as good as the It’s Always Sunny crew. But why are you insisting on playing the game on hard mode?4

And studios know this. While endlessly exclaiming that “audience tastes have changed,” streaming services know that audience tastes haven’t changed. No matter what I watch on Max – which are usually foreign films in black and white because Max has the greatest film library ever – they then say, “We think you would like to watch Friends.” Yet, they refuse the idea of just making shows like Friends.5

But again, this is all just part of the same problem that Left Behinding is, and the fatal flaw in my anti-Netflix argument. These huge media companies became huge because they once understood something they’ve now forgotten and only the tech company eating their lunch is willing to embrace: the key to succeeding in business is to give the people what they want.

Are there people who want prestige dramas? Sure. Are there people who want 13-hour movies? Sure. Are there people who want shows where characters literally turn to the camera and give political sermons? Sure. Are there enough people who want those things to avoid losing billions of dollars? Don’t seem that way.

Give the people what they want. What they want is not complicated. The most watched drama on American television is Yellowstone and the most watched comedy is Young Sheldon.6 A classic sitcom and an updated version of the prime-time soap opera like Dynasty, but better than that terrible reboot of Dynasty.7

Of course, the promise of streaming was that we would move past that. It was to be a golden age of content. But that age never dawned. I was fooled by this, and I should have kept my eye on the ball. Unlike the big media companies – or Apple or Amazon or Alphabet, all involved in streaming – Netflix is the only streamer who needs to be successful. A whopping 90% of their revenue comes from one source: subscriptions. As such, they have to give the people what they want.

This article is long enough – the original version was almost 4,000 words – so I’ve cut a lot which is a shame because streaming is a window into so much of what this newsletter is about. And there are a lot of issues I had to gloss over. These include the value of branding, the value of the user experience,8 and perhaps most interesting to me, the clash of old technology versus new. I refer to the AANGs as tech companies but then, what the heck is Comcast? What was Warner Brothers or Paramount? The clash between old tech companies and new is an endlessly fascinating look at where our world is headed. There are so many things going on other than just the content but, at the end of the day, these companies are in the business of distributing content. So, the quality of that content is – no pun intended – paramount. And even more than that is all business is simple: give the people what they want. As long as Netflix continues to do that and the others choose to do whatever the hell they’re doing, I’m going to keep being wrong. But now, at least, I can claim to be right no matter what happens. And at the end of the day, isn’t that what matters?

I would also argue that in addition to being better art, Tolkien created better Christian art. The same is true for politics. So, any politically motivated scriptwriters reading this, know that you will do a better job both artistically and politically if you’re more subtle about it. You know what subtle means? Laid back and shit.

I have of course done this. Repeatedly. Why aren’t you doing this right now?

Yes, “Long Term Parking” is beloved in part because it’s the end of a beloved character’s story, and what happened to her is part of a long arc. But rewatch the episode. All of that is handled as backstory, it could’ve been dispensed with in two lines of exposition. You don’t need to have watched all the episodes to appreciate this one. It just makes it so much better. That’s the difference between television and a movie.

This is often the part where people lose sight of the point that I am talking about usually, not always. Can you put out a quality 10-episode sitcom or drama? Absolutely, Apple TV+ did both with two seasons of The Foundation and Ted Lasso. But just because it’s possible doesn’t mean it’s likely.

As a minor irony, Paramount subsidiary CBS once had the brilliant idea of airing a show many considered a Friends knock-off. That show was called How I Met Your Mother and it made CBS a lot of money and, even despite its awful finale, is still more popular and beloved than any show on Paramount+ which, of course, refuses to just make shows like Friends.

A quarter century earlier those shows would have been Seinfeld and ER. The utter collapse of quality in popular entertainment is fascinating.

To Paramount’s credit, they are increasingly turning over their service to Taylor Sheridan projects. I find him hit or miss but you cannot deny that he understands what people want to watch.

I had a very long part about how Netflix has the only good UI, but it devolved into me complaining bitterly. But I really, really, really hate the apps for Max, Peacock, and Paramount+ and if you’re someone who works on those, know that I don’t blame you and imagine that “make it easy for people to access our content” was about 98th on the priority list for your bosses.

Fantastic analysis.

Also, this is only extremely tangentially related, but I don’t have anyone else to complain to, so… I think Amazon is nuts to have introduced ads to their Prime material and then demanded viewers pay a special fee not to see them. That’s TERRIBLE consumer psychology. They could have raised their rates and I would have grumbled a bit but paid it. But now it feels like I’m being held hostage for three bucks a month, which makes me feel resentful and unwilling to pay. And the net effect is that I’ve stopped watching Prime material completely. And I might just ditch it for something like Paramount+ or Max.

Just seems like an insane business decision.

It really is remarkable how bad every streaming app is except Netflix. Like, how do you hop into streaming a decade late and make an app that's basically useless?

What's been interesting is seeing these studios begin licensing their shows and movies back to Netflix, reversing decision on making their studios into gated neighborhoods where you need to pay a subscription fee to enter.

I think Sony is the ultimate winner of the streaming war. They've quietly licensed out their shows and movies to the big streaming services (sometimes several at once) while never investing the hundreds of millions into developing their own streaming service.

Rather than dump all that money into a terrible app that barely works, they've just been making money with their libraries. Also, hilariously, their competition in the gaming space is Microsoft, a trillion dollar company, that can't seem to win. Microsoft could BUY Sony for far less money than it would cost to compete with them, but instead Sony just drinks their milkshake every day.