Here's My Solution to Climate Change: Part VI - The Explosive Finale

In which we really hope there's nothing explosive about nuclear power

So now, after numerous weeks and countless words, far exceeding what I originally intended, where do we stand? Well, we agreed that if you believe climate change is a problem worth addressing that it is a problem that should be addressed in a manner calculated to be effective, not one that just makes us feel good or accomplishes other goals. And we agreed that if you’re looking for an effective approach, it’s highly unlikely that we should pursue the incredibly unlikely approach of trying to get humanity to unprecedentedly abandon all sorts of good things on the vague hope that it will benefit the distant future. Instead, we should focus on trying to build alternatives to our current systems and make them better what we already have, because people like better things. And we agreed that government – which is somewhat responsive to public opinion and very responsive to the people who can keep them in office – are unlikely to suddenly force us into solar powered pods where we eat crickets and are more likely to be an impediment we need to overcome to get those better things out there. So, we’re done, right?

Conspicuous by its absence in this series has been our old friend nuclear power. This isn’t exactly a novel observation. If I may digress a moment to speak of the perils of being an unknown, I remember when I was in my second year of law school – aka a 2L – and I spent many months working on what was undoubtedly the best piece of writing I’ve ever done, my case note for our law review. I was well on my way to publication, which could have changed the entire course of my career. After submission – but before the publication decisions were made – an article on that exact case dropped, in Harvard Law Review of all places, written by one of the foremost experts on that topic, someone I extensively cited, in fact. I remember my esteemed faculty advisor telling me that the good news is that my analysis was proven to be correct, the bad news is that no one would ever publish it. Being right while getting absolutely no benefit from it, a lifelong tradition.

I thought about this a few weeks ago when a far more famous author wrote a piece making the same basic argument as this series except with the talent of one of the best writers working today.1 Okay, well, it happens. Then, after having this week’s piece on nuclear power and the role of climate activists in stifling it was written and scheduled for publication, my Twitter feed turned up this article being published on a far larger website that, well, it’s definitely not the exact same as my original piece – I promise to never use a movie as a framing device – but there’s enough overlap that it was time for a last minute rewrite. Again, it always pays to be big and never pays to be the little guy.

But, alas, I promised you for weeks that I’d be wrapping this series up today and doing so by talking about nuclear power. So, it’s time to pivot, and we’ll pivot away from discussing climate scientists and activists and politicians to what the core of this Substack is about: the intersection of technology and the public. This one will be a little rough, so bear with me.2 And the good news is that the Quillette piece already covers a lot of the background on the role of nuclear as well as the role of climate activists in stymying its adoption. Which means I can skip right ahead to the meat. And the meat is this basic contradiction: if I am hanging this series on the concept that people adopt better things, and nuclear is better, why don’t we use nuclear? The problem here seems to be that I never actually defined better.

If I was given the power to remove one technology from existence I would not have to guess twice: scooters. I hate them. You may think this is ridiculous, and there’s so many other options that would be better to eliminate. Some of you may be furious I didn’t choose guns. Some of you may think I should’ve chosen nuclear weapons. Some of you may make the argument that this setup allows me to remove COVID-19. Those are fine answers. But I don’t viscerally hate them the way I do scooters. I like being a pedestrian and I like taking my dog on walks through the city. It’s part of why I spend far more money than I should living downtown. These things make life a living hell. They’re strewn everywhere, driven recklessly, and are a general menace. I wish they would disappear forever.

But about 20 years ago, there was immense hype for a product that we were told would revolutionize transport. This was turn of the century, so we still had excitement over new technology that wasn’t some variation of “let’s you use the internet.” We were all disappointed when it turned out to be the Segway. If you don’t recall their initial launch, you probably know them solely as those things mall cops3 and tourist groups use. But they were generally hyped (before the public knew what they were) as an invention that would rival the personal computer. They were met by achieving a whopping 1% of their sales target in their first five years. A disaster of historic proportions.

So why did the Segway become a punchline while twenty years later our lives are cursed by the plague of motorized personal transport? Clearly, the idea that “it was a solution in search of a problem” was not accurate. A sizable chunk of the population does in fact believe that wheeling somewhere is better than walking there.4 The problem is that even if you accept that as “better” there were other elements that made the Segway, in the eyes of the public, not better than walking. For starters, the price. These things were an expensive upfront investment – unlike the cheap “pay per use” model of the electric scooters. Secondly, they were big and bulky and where would you even park them? They weren’t like the little electric scooters that people feel completely comfortable leaving strewn around the city inconveniencing everyone. And – in a point that I feel can’t be undersold – they were dorky. They were bulky and looked ugly and if you used one you had to buy one from a dealership and become “a Segway person.” Who wanted to do that?

History – even just during my lifetime – is replete with examples of technologies that were better than what we had but just failed. Some – like virtual reality – were just ahead of what the technology could provide at the time and are still being pursued. Some – like the McDonald’s Deluxe line – were unable to convince the public they were better but achieved success in other forms.5 Some – like the Dvorak keyboard – were better but not so obviously better that they could overcome the inertia of what it was trying to replace. And some – like the Ford Pinto – were better in some ways but had some horrible drawback, like being death traps, that made them a net negative.

That last one is most relevant, because the idea of “better” is based off the public perception. And if the public perceives something as having some major drawback that makes it not better, that’s going to be difficult to overcome. And unfortunately, nuclear has one big drawback: the perception that it will kill everyone. It probably doesn’t help that the public’s introduction to nuclear was in the form of a bomb that annihilated a city and killed a lot of people. But even the energy itself is scary. I lived near a nuclear power plant and although I didn’t think of it often – it was about an hour away from me – the times I did drive past and it see those cooling towers, I won’t pretend I didn’t think twice. I am not alone:

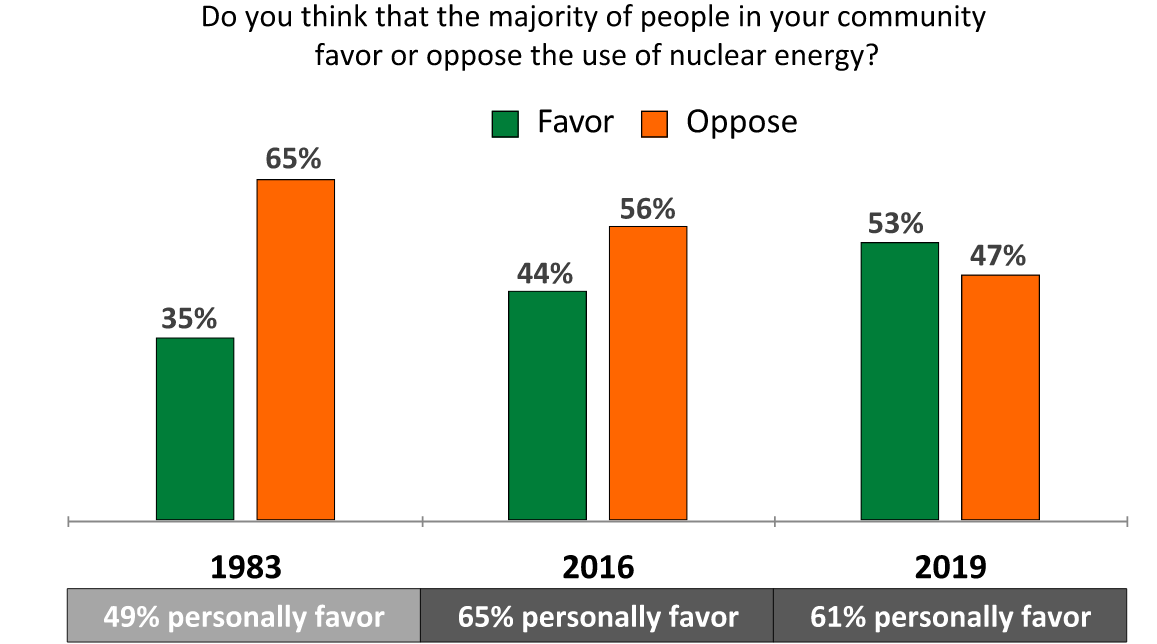

The above image comes from this very long article about public opinion on nuclear energy and triggering events. The red line tracks the public support and – although it was already going down during that terrible decade of public opinion known as the 1970s – the Three Mile Island disaster did not help. Nor did Chernobyl. Nor did Fukushima. The story here is essentially that a lot of annoying people in the Decade of Dumb convinced the public that nuclear was dangerous, then they were given an example of it. Afterwards, every time public opinion was on the way to recovery something bad happened. That’s why even today, probably only about half of Americans support nuclear power.6 But the most interesting part of this is – and as I said in the footnote, this is an industry source so grain of salt here people, but I think the data is worth discussing – this chart:

Even though this is from the people who want you to adopt nuclear, it’s such an interesting framing that I struggle to see why this would come out differently. A million years ago – or 1983, same thing – people assumed everyone hated nuclear power. I’ve referenced The Simpsons here before in part because in the late 1980s and early 1990s this was one of the few portrayals of nuclear power in popular culture. The butt of the joke was that the power was not safe. This was such a commonly accepted position that you could base a major part of the show around it. If this data is reliable, it’s an interesting situation where people’s own preferences are out of line with their perception of other’s, indicating that a lot of the fear of nuclear may be driven by a general belief that you’re supposed to fear nuclear.

As interesting as that may be, does it change the bottom line? Not really. It is likely that another nuclear disaster could spur a big public opinion swing away from nuclear but what’s going to spur a big public opinion swing towards it? It appears that we’re just on a slow march towards acceptance. Perhaps the further development of small modular nuclear reactors – which the Chinese are already making headway on – will cause excitement and acceptance. And, although I refuse to discuss it at all in this newsletter, ya know, there’s always the possibility of a nuclear fusion breakthrough7, something so hyped that its occurrence could significantly swing public opinion. But otherwise, it is unlikely to be a public outpouring of pro-nuclear sentiment that will drive this.

But see our earlier discussion on political sensitivity. It is going to be the well-heeled people behind nuclear power who are going to be driving political support for it. And there’s a dire need for that, at least here in the States, where approval for new plants is quite difficult to come by. Which means that elite opinion on this is something to monitor. For the last few months, I’ve been bookmarking every article I saw about the growing excitement for nuclear power in anticipation of writing this piece. In the end I gave up because there were too many. There’s been a change in how nuclear is being discussed and that’s good. Public opinion does not need to drive this, we don’t need people getting nuclear symbols tattooed on their chest. What we need is enough support that, say, a member of the West Virginia House of Delegates or a government official in Wyoming or Tennessee or the United Kingdom can support new plants or reactor research without fear or being accused of wanting to Chernobyl their constituents.8 And it seems that we’re headed in that direction.

To stay on broad, I’m broadly optimistic about the future of nuclear energy. I also don’t think it is the entire ballgame. As I’ve said repeatedly, it will be a buffet of options that helps us overcome this challenge. But optimism should never fall into its dark version: pollyannaish naivete. There’s a lot that we need to do to make this optimistic vision happen. We see with nuclear power that just creating an alternative means nothing. There needs to be broad public buy in, which means this isn’t just up to battery innovators and nuclear engineers. It’s up to all of us.

This newsletter has grown a lot during the course of this series. First, I appreciate each and every one of you for your support, it genuinely means a lot to me. Second, beginning next week we’ll go back to my original conception of some one-off pieces. I have another long series I’m working on but it’s taking a bit more time than expected, so if anyone has ideas, I can’t promise I’d write about them but I’m always interested in hearing.

I had also started working on a piece on the “build a bigger Manhattan” proposal but I may shelve that as well.

I’m an ardent believer that you write and then you edit. These pieces are usually a third or fourth draft, with even the first draft being written over a long period of time involving numerous long walks with my dog to work out ideas and my great nemesis: conclusions. Today I have not done that. This is pretty much a rough draft, written stream of consciousness starting earlier this afternoon. I apologize if it comes across as rough.

Many of you younger readers are confused right now what a “mall” is, which I recommend googling or watching the documentary Paul Blart: Mall Cop.

As much as I detest these things and refuse to ever use one, I can obviously see the utility. I live in an incredibly safe city but there’s definitely times at night I’d prefer to not spend a half hour walking home when I could just scoot there in a brief amount of time.

This was another marketing fail, where McDonald’s launched a huge marketing campaign based on McDonald’s becoming “more adult” with weird but intriguing commercials of Ronald McDonald doing things like shooting pool. Then it turns out the campaign was just for a new line of sandwiches, headlined by the Arch Deluxe. These were considered a massive failure, and they were. Except, only if you define failure in the traditional way. This was actually a massive long-term success in diversifying McDonald’s product line into the type of higher quality food they wanted to sell to capture that market. The Chicken Deluxes sandwiches were a failure until they were brought back a few years ago to (successfully) improve the now established premium sandwich line. The Fish Filet Deluxe was a failure except when it was dropped the patty was used for the legendary Filet-O-Fish, improving that sandwich. And the overall strategy was later recycled to launch the successful salad line.

Sometimes headlines will be made that show much higher numbers but they’re from industry sources so, yeah, I wouldn’t put as much stock in them. Ironically, I’m about to cite an industry source but it’s because the data is so interesting it’s worth it, just take it with a grain of salt.

It’s impossible to discuss this issue without the “yeah, yeah, yeah, we’ve been hearing about this for decades.” So why even bother? I genuinely believe that there is hope for this. But I’m not going down this rabbit hole publicly.

Long footnote: Because I didn’t need to cover a lot of the stuff in the Quillette article I didn’t spend much time talking about the villains in all this: the Germans. However, events change all things. The looming Russia/Ukraine crisis is interesting here. As that earlier analysis revealed, energy insecurity drives opinion on nuclear power. Germany is already dealing with energy insecurity and are highly reliant on Russia for their energy. Anything that leads to a disruption of that could throw Germany into quite the energy insecurity. It will be interesting to see what happens to German public opinion on nuclear if there’s no cheap and easy supply of Russian natural gas for them to pump into the atmosphere.

I feel the pain of being a close second. In fifth grade I kept a steady pace and was 20 yards from finishing first in the field day mini marathon but KERRY BEATTIE’S MOM who WORKED at our SCHOOL ran out and cheered her along right beside her until she passed me with literally ten feet to go. Yeah I did great, but second place didn’t get your name engraved on the plaque in the office now did it?

Ahem.

I have a lot of notes. 1) I run a Segway dealership so how dare you.

2) I’ve never had the filet o fish because I’m scared and I KNOW I like the burgers so why take the risk?

3) In The Expanse the fusion problem is solved by an invention called the Epstein drive (not a spoiler, just an interesting piece of world building).

4) I really hope people get their heads out of their asses about nuclear energy. Yeah there are some notable disasters in the past. But compared to other types of energy? I mean come on. Maybe this isn’t a great comparison, but it makes me think of self-driving cars. Yeah there have been a couple accidents, but compared to human drivers? It’s not even close. So now we’re getting the tech in drips and drabs (auto parallel parking, auto emergency braking, some semi self driving features) to ease all the butt beads into the tech. Which, fine. But how do we ease into nuclear energy? Your reactor is running or it ain’t.

Edit: butt HEADS not butt beads. That’s a different kind of post.

Hello DanT. I came upon your Technopoptimism and decided to start with this six part manifesto about Climate Change. This was great writing and the optimism part works for me (based on the title of my Newsletter -- no self promotion and no links I promise). I am a retired engineer who spent his career at a scientific firm, nuclear power generation, and later in food safety and service. I look forward to reading a bit more of your stuff but just wanted to say how your optimism is an important ingredient and might keep me coming back.

I probably disagree with parts of your theses in these six parts but that is reasonable since it was pretty broad. I will say, with a fair amount of expertise and experience, the underlying challenge, and "the failure to launch" for light water reactors everywhere is that they never got on a learning curve. There has never been an innovation, continuous improvement model that made such a thing possible. Continuous improvment and trial and error is the root of innovation but in cases like fission and fusion the risk/reward makes fashioning a learning curve near impossible. An example of the difficulty is the realization that 75 years of nuclear warhead design has likely only resulted in one or two breakthroughs. This is not a learning curve, but rather a very slow waterfall development model. I fear people do not often drill into root causes of things b/c it can be boring and laborious. I have rarely, if ever, seen a cogent lessons learned from Fukushima and the reality is the fundamental design of a GE BWR presents an existential risk that happened to align for coastal Japan. On a broader level, however, I think your outlook is the only of the four possibilities you present as having a chance to succeed regarding atmospheric gases and their impact on the climate. While it is not the greatest word for explaining the climate challenge, entropy is the singular issue, if one exists. Thanks so much for writing.