I estimate anywhere from one-third to one-half of the people reading this came – in some way – from Freddie de Boer’s Substack. Although I may not share Mr. de Boer’s brilliant writing talent, or wide range of topics, or sizable readership, I do share one thing with him: we were both Marxists in our youth. And although, unlike him, I no longer am, it does mean that I am well-versed in dialectical materialism. If you aren’t, the short version is that it is the philosophy underpinning Marxist philosophy. Derived from Hegel – whom, in full honesty, I could never quite make my way through – it’s a method of interpreting the world based on the idea that everything is constantly changing. I assure you that I am not here today to either try and fully explain dialectical materialism, convince you of its truth, or defend it. And I’m certainly not here today to drag this newsletter down into a morass of philosophy for which I am woefully unqualified to discuss. Instead, I’m here because of stirrups.

History consumes about two-thirds of all my book reading1 and recently I finished the absolutely phenomenal Power and Thrones by Dan Jones.2 This enthralling history of the Middle Ages is one of the best books I’ve read and I could probably have written an entire piece just on the various lessons from that book that still fit into this theme. And the discussion of the development of knights made me think of a less scintillating read: Dialectics of Nature by Friedrich Engels. Because there’s a strong chance that you spent your teen years having fun and not reading obscure Marxist literature, allow me to begin by explaining its relevance.

In Dialectics of Nature Engels articulated three fundamental laws of dialectics. The first of those, and the one I always found the most interesting, is the law of the transformation of quantity into quality (and vice versa). Briefly, the idea behind it is that many small changes – although not particularly powerful on their own – combine to become a qualitative change. Think about the boiling frog, which I suppose leads me back to the beginning of medieval history. There was no one moment when Rome fell and the Middle Ages began. It was just numerous small changes until there were so many changes that a phase transition occurred and you were no longer living in Antiquity.

Why is this relevant? Because between the 10th and 12th centuries there was a massive shift militarily in Europe into the age of the knight, one of history’s iconic military figures. There was nothing new about cavalry, humans had been riding horses for a long time and once we figure out how to do anything we find a way to use it to kill. Even the Romans – the paramount infantrymen of Western Civilization – had cavalry, including heavily armored ones. Charlemagne – just a few centuries before the period we’re discussing – had armored, spear wielding horsemen. But they still didn’t have knights. Why? Technological change.

Four separate pieces of technology all proliferated in the West over the period of a few centuries. Arguably the most important – and when I say arguably I mean there’s heated arguments over it – was the stirrup. These allowed riders to stay in the saddle longer and fight harder. There was also the couched lance, which was able to be stationed under the arm and provide more attacking power. There was the cantled saddle, which did a better job of holding the rider in place. And there was the rowel spurs, which allowed greater control over the horse. All of these technologies proliferated over the period of centuries. You can find cavalrymen using some of these well before knights. But once all of them were linked there was a phase transition, a qualitative change.

The transformation of quantity into quality is core to technological innovation. All technologies are, like Isaac Newton and Oasis, standing on the shoulder(s) of giants. Even this wonderful little tool we’re using to communicate right now is a perfect example. In the thirty years I’ve been using it, the internet has undergone numerous qualitative changes. But how many of them were singular qualitative leaps? It’s been uncountable small improvements until you realize the internet of the 1990s looks unrecognizable.

A lot of what we view as disappointing – or even failed – technology isn’t failed, it just hasn’t gone through a phase transition. Let’s look at this list of the most disappointing technologies of the Oughts. Allow me to preface this by pointing out that the writer of this knows far more about computer technology than I ever will, and has made far more of a contribution than I am ever likely to. My days at work are haunted by the hellish but useful technology he created. So this is not a ”let’s laugh and point” expedition, as hindsight often makes things look. The analysis appears dead on, particularly as you scroll through it nodding at the disappointment of things like satellite radio, PDAs, and the Nokia N-Gage (which deserved to die just for the name and this commercial).

But then you hit Apple TV, green cars, and something he calls the music revolution, and we see how quickly things can change.

We’ve talked at length about green cars. I’m writing this while watching Apple TV+ on my Apple TV. And although it’s not the market dominating success Steve Jobs may have hoped it would be, that’s only because there’s so many competitors, not quite the graveyard of empires that set top boxes appeared to be. In part this was because the technology kept getting better. But perhaps most importantly, as we’ll (hopefully) discuss next week, the streaming revolution occurred. Instead of buying shows off iTunes, you were consuming most – if not all – of your media through streaming. If the Apple TV was simply a fancy DVD player, I wouldn’t own one. Instead, it is a full replacement for my cable box. The technology wasn’t a disappointment, it was just waiting for its complementary technology.

As for music? Well, here’s a nice riposte to that:

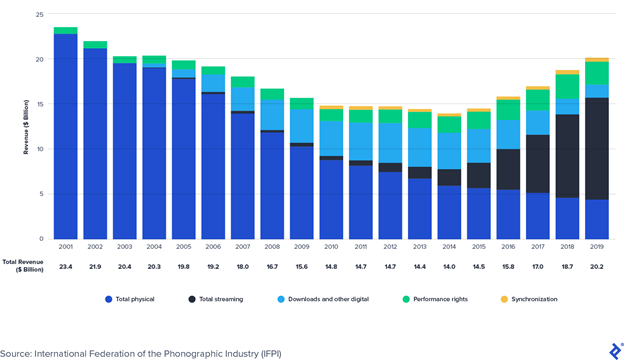

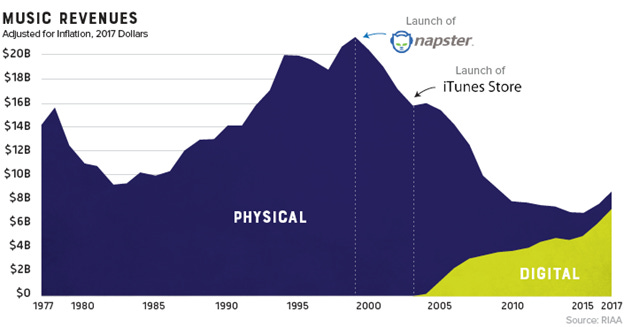

Basically, the 1990s – also known as the greatest decade in human history – was a golden age of music industry profits. That’s because compact discs were a giant scam. Remember paying $20 for an album? Then along came Napster and the music industry – as that author rightly points out – spent the better part of a decade fighting against the future. But then, yes, the music industry started working with innovators. And look what happened. Here are two other charts that illustrate this beautifully:

As these show, the music industry is not back to the halcyon days of the 1990s. And those decades of riches for the musical artists are long past. But as a consumer? It’s no overstatement to say this is the best moment in human history to love music. When you consider music is about 40 millennia old, that’s saying a lot. I have the option to purchase incredibly high-quality audio recordings. I also have the option to instantaneously stream a ludicrously high percentage of all recorded music. And it only costs me monthly the inflation adjusted equivalent of a third of what I paid to buy Bush’s The Science of Things in 1999.3 And yes, that’s more than I paid for Napster, but this is instantaneous, requires no downloading, no storage space, and no illegality. When has it ever been better?

The (often incremental) improvements in underlying technologies. New business models. Changing public attitudes. Combined they can drive the most disappointing technologies into successes. Spotify and Apple TV may not be as important as knights, but other disappointing technologies may be.

Cryptocurrency is probably a little closer right now to “scam” than to “societal changing technology.” But maybe instead of declaring it a failure, we need to be asking what’s the complementary piece – or pieces – of technology missing? Is it an engineering problem? Is it a social or legal problem? Is it that crypto’s real purpose will end up being supporting something else? It’s hip to trash crypto right now and, hey, I get it, I used to follow Balaji Srinivasan on Twitter too. The level of P.T. Barnumesque bullshit coming out of that space is so nauseating my next series I’m working on is about this problem. But let’s hold off on declaring it all a grift or a failure.

We could say the same things about other technologies that develop the air of disappointment. Not to make this the Autonomous Vehicle Substack, but we’ve been hearing about them for a long time. These are perhaps a perfect example of a technology undergoing incremental improvements. We can’t anticipate when the phase transition will take place. The same with nuclear fusion. The same with virtual reality. And on and on.

For example, 3D printing. This technology is probably a bit older than you may think, but it has only truly entered the public consciousness in the last decade. On the one hand, you have people extolling its revolutionary power. Did you know 25% of the buildings in Dubai will be 3D printed by 2030? That’s a fantasy, but even less insane people do believe that 3D printing could solve some important problems, like housing,4 medicine, and, most famously, easy access to firearms. On the other hand, you have the reality of 3D printing which is, not as encouraging. It’s a good technology but lagging far behind expectations people had even seven or eight years ago. It’s the kind of thing that’s easy to chalk up as a disappointment. However, if, like me, you live in a tech hub, it’s impossible to throw a rock from your overpriced, tiny apartment and not hit either a Californian, someone really into NFTs, or a company trying to improve 3D printing. The one I linked to there, Accelerate3D, is my local one and they’re trying to 3D print ten times faster than current printers. Will it work? I don’t know, no one does. But if it does work, is that the kind of change that, combined with others, can produce a qualitative leap in 3D printing? Again, no one knows. But if we had a qualitative leap in 3D printing technology would it benefit society? Absolutely.

This comes down to a push and pull between hype and reality. We have a culture where – for financial reasons – those in the tech industry will hype things up to immense proportions. Remember the Segway we talked about a few weeks ago? And the tech media of course goes along with this, because, hey, it’s better for clicks if you hype something. Then, unless it’s an iPhoneesque instant success, it gets trashed. Which, I get it, that type of things drives eyeballs. And, to end the piece in the place I started – by referencing Freddie de Boer – it’s a lot easier to trash things and maintain a style drenched in irony. Look at the Metaverse. Sure, it definitely looks stupid, it feels pretty stupid at times, there’s a good chance it’ll fail, and Mark Zuckerberg isn’t exactly the kind of guy you root for. But, really, we’re going to gleefully declare the Metaverse a failure already? Really? The first of those pieces is particularly deranged, featuring quotes such as this:

Our brains are wired to view images and process information in a particular way. Electronic technology has greatly expanded the range of what we can experience. However, after several decades of consumer engagement, we can start drawing some conclusions as to what we’re comfortable with. And the metaverse isn’t it.

Like a judge denying a motion I wrote that I had no evidence for, I’m going to declare that “conclusory.” Yes, betting on things to fail is smart, but the correct reasoning is “most new business ventures fail” and not whatever that word salad is. I get why journalists who write about tech5 do this. No one wants to be the eager beaver getting sucked into hype. And the metaverse really does seem dorky.6

But, is that the kind of society we want? One that takes a dump on the cantled saddle because “all it’s doing is letting you sit a little better on a horse, big deal”? Or one that realizes we’re always just that one small improvement or that one small combination away from changing the path of history? That at a certain point quantity can become quality, and we’ll see a phase transition. Any innovation may, someday, change the world, and we open up more possibilities if we look at it that way.

Except for Roombas, those things will always be trash.

My mother will still occasionally voice her disappointment that I became a lawyer instead of a history professor. There was a span from about 1998-2000 when it seemed like I was absolutely going to follow that path. Although I would’ve enjoyed not having to work in the morning, I feel like I’m glad I’m not currently in academia.

Highest recommendation to buy. And although I’ll use the word “read” I chose the audiobook version because he has the perfect voice.

I tried to pick one of the most random albums I bought for full price as a teenager, but also one that I’m willing to admit I bought. This is an underrated slice of Bush’s discography. Nowhere near as good as Razorblade Suitcase but it holds up much better than the more famous Sixteen Stone. Greatest. Decade. In. Human. History. I also chose to link to Letting the Cables Sleep because it’s better than The Chemicals Between Us and, frankly, I need to boost the numbers on this Substack if I’m going to keep doing this. That video has a lot of topless Gavin Rossdale so I better see a large bump in the “40 year old women who were into alt rock in high school” demographic.

I should note that this is kind of the main thrust of this entire Substack. It’ll be wonderful if we can 3D print quality homes. It won’t mean anything if you can only build them in a field in Kansas. The chokepoint with housing is legal and political, not technological – at least in the United States.

Which, let’s be very clear, I AM NOT. I am a bored lawyer who writes about the intersection of technology and society. Which means I have no expertise in either journalism or technology. I imagine most of you stick around for my smooth 90’s pop culture references. Uhh, Nash Bridges. There ya go, there’s that sweet nostalgia dopamine.

I genuinely believe there’s a chance it could re-revolutionize retail. I don’t believe it enough to not bury this in a footnote, but I don’t see why a virtual mall, or a virtual main street, wouldn’t be a qualitative improvement over current online retail. We’ve become used to them but the online retail interface is orders of magnitude worse than the real world version. I see a lot of excitement over “oh, you can buy an NFT of clothes and have your person wear it!” and I’m thinking I’d much rather use the metaverse to buy actual clothes.

Another home run; well done, Dan

If you were a 90s kid and interested in history, you may remember a TV series called "Connections" where a historian goes through and pulls together all of the unlikely and unrelated things that had to happen in order to reach certain milestones. It's the same theme you're on here.

As for some of the new finance-related things that seem to have not found their legitimate use yet, Matt Levine is someone to follow. He puts out a newsletter a few times a week. He's attached to Bloomberg,(so unless you wanna plunk down a subscription for that, there's no way to support him) and while it's ostensibly investment advice, he's a good writer following Wall Street (where many of the biggest decisions are being made).