School's Out

Why the MOOC future still hasn't arrived

For someone who is essentially a futurist, it can be confusing to others why I’m often very critical of what I see as over the top predictions of what technology can do. I don’t view this as a contradiction. That’s because I believe one of the biggest hindrances of technological development is public cynicism caused by overhyped failures. Nothing since the fall of the Western Roman Empire has been a bigger detriment to progress than disappointment by the lack of those damned flying cars. Less hyperbolically, public reception of blockchain based technologies will be slowed by the very public collapse of crypto and NFT speculation. This process of overhyping something and then watching it land with a whimper – or Segwaying as I call it – is not just the province of fanciful, misused, or just plain stupid technologies. Sometimes it happens to a genuinely promising technology, just like it did with MOOCs.

MOOCs, or “Massive Open Online Courses,” were a fad of the first half of the last decade. Designed by people who clearly didn’t know old-timey insults, they took the kind of top quality learning found in the world’s most prestigious universities and put it out there for anyone with the will and high speed internet. The New York Times was replete with headlines like “The Rise of MOOCs” and “The Year of the MOOC,” and those were some of the more restrained pieces you could find. These things were hyped as being the future of education. Flash forward to today, and it seems like the future is not here yet. But why?

In theory, MOOCs are a great idea. I try to keep this space as free from partisan politics and culture warring as possible. But I think no matter what side you’re on in those things, you can easily come up with a reason to agree with the premise that it would be good to free education from the shackles of universities. I’ll be long in the cold, cold ground before I comment on a hot political issue here, but I seem to recall a lot of discussion about student debt recently. College is expensive. Meanwhile, I can take the Harvardx’s Introduction to Computer Science or MITx’s Introduction to Biology for free – with a nominal fee to get proof of that. This seems like harnessing the things we’ve gotten good at in the last quarter century – digital communications – to turn what was once an incredibly scarce resource into an abundant one, lowering the cost. All while helping with a societal problem and creating a more learned, education population and workforce. It’s popular to crap on the idea of how the internet promised us a brilliant future but instead it’s somehow made things worse. Yet, it seems like I’m looking at exactly that brilliant future in the form of MOOCs. So why didn’t this work?

There’s the simple answer, common with many disruptive technologies: the thing that MOOCs were supposed to disrupt wasn’t based on the thing your technology disrupts. As I’ve said before, Uber and Lyft could dominate the taxi business because they replicated the one thing a taxi gives you: the ability to get from one place to another. MOOCs couldn’t dominate the education field because the value of universities isn’t in providing learning. And this isn’t the preface to a Peter Thielesque jeremiad against colleges.1 It’s that economically, colleges don’t derive their value from providing you something you could get for a dollar fifty in late charges at the public library. They derive it from providing credentials that allow people to access money and prestige. MOOCs cannot offer that, and it’s unlikely they ever can.2

Unfortunately, the “funnel everyone who does remotely well into high school into college” model is probably a suboptimal way to run society. For more on this I would recommend reading last week’s entry from Certified Friend of the Stack Mari – and really you should always be reading Mari – on academic tracking and creating an educational system that optimizes happier lives and better outcomes. I also think that this strongly relates to the issue of how this chart happens.

And this isn’t just about student debt. There’s a far larger issue of the sort of talent we lose out on as a society because they haven’t followed a specific path, one that mainly begins as a teenager. It would take a much deeper dive than we have space for here3 but this is possibly part of the great stagnation that’s occurred over the last half-century. The explosion of progress in the 19th Century was not spurred by credentialed individuals, but by people from all over society. Lost societal contribution because we decided everyone should go to college would be quite sad. And worse, it’s nonsensical. Because if I asked why we endow people with prestige and money for going to universities, it’s difficult to answer without falling back on “because that’s how it’s done.”

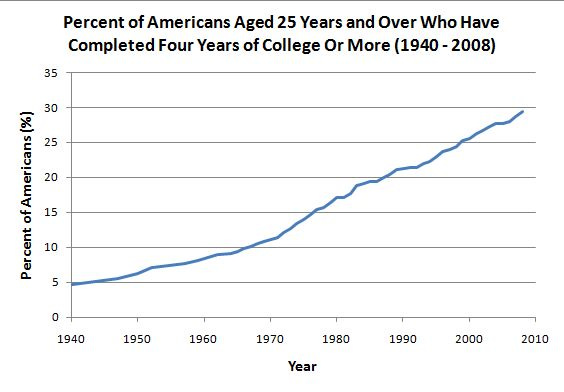

Let’s start with why it’s more prestigious to graduate from college than it is to learn all knowledge. Here’s an easy pair of charts.

It used to be rare to go to college. Heck, most people didn’t finish high school. It’s unsurprising we’d view this as prestigious. In 1800 there were only 25 colleges in America. Six decades later there were still only 241. An illustrative fun fact is that from 1829 until 1901 only two U.S. Presidents attended an elite college. In fact, half never even graduated college. This was a rare achievement – highly correlated with class – that we endowed with great prestige. This is also probably why elite colleges are considered elite. As a quick and dirty way of thinking about this, look at the US News & World Report ranking of the Top 100 national universities. Their average founding year is 1858. But what’s more interesting is that if you cut it to the Top 50, it’s 1842. The Top 25 is 1827, and the Top 10 have an average founding year of 1810. Clearly there’s some correlation between prestige and how long it’s been around. It’s impossible to say whether Harvard provides the best college education in America. But it wasn’t in 1636. Because it was the only one around. Impressions, once formed, last for a long time.4

But prestige isn’t everything and, frankly, we could probably ignore it. If people want to pay a premium to have other people think they’re smart, that’s no different from any luxury good people buy to impress other people. The rubber really hits the road when we get to access to money. The main reason people go to college is to get a good job. And that raises the question of: why would an employer care?

There’s a lot of reasons why employers value degrees and value them the more selective the school is. The first is that it may be a good gauge of someone’s intelligence. After all, they had to be pretty smart to get into Columbia! But that reasoning seems quite tortured. Firstly, you’re essentially assuming this based on SAT scores. And yes, there’s correlation between SAT scores and getting into college, particularly selective ones. And there’s a correlation between SAT scores and intelligence. Thus, you have a twice removed correlation with intelligence. But you know what has a direct correlation with people’s intelligence? A test of their intelligence! If you’re using college as a proxy for intelligence, you may be picking a much harder route than needed.

The “college degree as a proxy for intellectual work” seems better but still a ridiculously imperfect metric. Certainly there’s easier ways to judge this considering that the actual level of work required to get a college degree is massively different from major to major and school to school. Particularly in an era of grade inflation. It seems like things such as work history would be more helpful. Plus, I assume someone who self-educates is pretty good at doing intellectual work.

Now, what about the idea that you want people to have specific knowledge and skills of the type learned in college. And, for some reason, you can’t – or won’t – test those things yourselves, even though we live in a day and age where LinkedIn can test my Excel abilities. Further, let’s say you also think instructors at the most elite institutions would teach this information the best. What if I told you there was a way that people could learn this information – taught by instructors at the most elite institutions – without attending an expensive school for four years? Congratulations, they’re called MOOCs.

I would not claim that MOOCs as they currently exist are a perfect substitute for college courses. The main problem being that they don’t have the same type of project and assessment based grading that many university classes do, referring back to the “substitute for intellectual work” argument. This problem seems both relatively easily surmountable and only relevant in select areas. Yes, there are professions where this is relevant – engineering the obvious example. But there’s probably many more fields where this is pointless and yet we continue to shove people into college.

If I can briefly digress into my field, law school is a microcosm of all this. We’re given what’s basically an IQ test to determine which one we go to. Prestige is highly correlated with age. The amount of law schools has exploded over the last century. Law school itself is a mess, a three year program that is only three years long because, uhh, that’s the way it’s done.5 The vast majority of states require that attorneys attend law school – many also require a bachelor’s degree or attendance at ABA approved law schools – which makes sense until you remember that’s not the requirement to be a lawyer. That’s the requirement to take the test to determine if you understand the law well enough to be a lawyer, which should tell you everything on its own. It’s just a mess of requirements built up over history. All of which took changing how we did things – which was that attorneys would read the law and apprentice. That’s how we got bums such as Abraham Lincoln, John Marshall, and Clarence Darrow. But that way of doing things is now so entrenched that changing it would take a revolution in legal education.

The same problem exists across higher education. But it’s even more ridiculous. If a law firm wanted to hire a lawyer, they need to hire one who’s gone through all those things I talked about. Employers in many fields don’t. In fact, many are already ahead of this, particularly in “tech” where a greater focus on skills in hiring exists than in many other fields. That’s why MOOCs – which is a great technological advance in learning – still could be the future of education. But only so long as education is viewed as a means of learning things, not as a vector to gain prestige and employment opportunities. And change there doesn’t take place at the education threshold. It takes place at the hiring threshold. You could convince the thousand smartest and most hard working high school students in each state to skip college and just take courses on Edx. And if you did that it wouldn’t change anything, people would just (unfairly) consider those kids weird and they would limit their job opportunities. The choke point is with changing how employers act and how with society thinks. It would require people to stop thinking about things as they’re currently done as being the only way, and start thinking about better ways to do things.

As important as education is to society, on the plus side, we’re not talking about lots of people dying. Next week, we’ll take a look at when the dead hand of history lives up to its name.

Unless Peter wants to pay me to say that. I’ll even go back and edit this piece. Just give me enough to afford a place in Malibu, that’s all I ask!

The first draft of this – written quite a while ago – explained this extremely well with a quite extensive analogy to college football. However, I refuse to use sports in back to back weeks so it’s cut. It also had a funny running bit about the University of Austin. But no one has heard about that in months so it’s not funny anymore. I assure you though, it was hilarious and you would’ve dropped your phone from laughing so hard.

Perhaps something book length. Wink wink, publishers reading this.

I have no reason to believe Harvard doesn’t offer a fantastic education, I should note. I also have no reason to believe Pomona College doesn’t offer a fantastic education. I have no idea why we’re all certain one is a superior education to the other.

The three year versus two year thing was a hot topic when I was in law school, and has still had almost no progress being made even though I’m now an old man. This also isn’t a fringe opinion of mine. Barack Obama, Alan Dershowitz, and Eric Posner are among the list of prominent people who think it should be shortened. But, change is hard.

One thing that's not mentioned here that seems apparent to me is that universities are social environments in a way that MOOCS are not. In my opinion humans generally adapt to the social environment they find themselves in so if you are a full time student at a MOOC you are in a very different social environment (home) that may be much less conducive to learning.

Very interesting take on things and worth a second and third read. Thanks for sharing.