If I had to make a list of all the actual benefits I’ve gotten from social media, it would consist mainly of a few products I’ve bought from Instagram ads and David Fincher’s underrated masterpiece, The Social Network.1 I’m not the kind of person who rails against it and calls Twitter a hellsite, but I also think it’s a generally a promising concept held back by a failure to create proper cultural norms around it and not something I care that much about.

Of course, on the internet – particularly on social media – having that kind of middle of the road opinion is about the most unpopular opinion you can have. In the internet age, not calling someone a Nazi is the new calling someone a Nazi. Thus, there are a lot of extreme opinions about how awful social media is. I tried to find a representative one but when I googled “how social media is” the autocomplete was so relentlessly negative I just gave up. And I think a lot of the hate is unfair. For starters, social media gets a lot of blame for just being a more popular version of the internet. Which I get. The early version of the web was a special place but every free 90 hours of AOL CD that was sent out made the internet just a little bit worse, to me at least. Social media does a great job of allowing people to easily use the internet. Yes, your uncle’s Facebook updates are annoying. But I bet his Geocities website would’ve been annoying too. It’s just that now your uncle – all the uncles, really – can have their own little website without putting in the work. So, although I believe there are legitimate criticisms of social media, they need to be distinguished from what are simply criticisms of democratizing and growing the internet.2

The most popular criticism of the internet over the last few years – probably since around 2016 – has been the issue of misinformation. There’s a lot of people – including important people and those who have control of the levers of government – who believe that Facebook and Twitter are destroying democracy and literally killing people by spreading misinformation.3 But what if there’s a different – and far worse – problem?

Allow me to reminisce about my pinnacle as a member of society: my time as an internet hockey writer in the 1990s. I’m typically a generalist, but in a rare flash of ambition, 13-year-old me saw a niche to fill and went for it. Hard. I’m talking like “Mark Wahlberg spending four years training and agreeing to get legit punched in the face for The Fighter” level of dedication here. This was pre-Google, pre-Wikipedia, pre-streaming video. I devoted hours to digging through boxscores, creeping on college messageboards to see if anyone was talking about the BU game, and tape-trading with people all over the world just to get a glimpse of a prospect. I taught myself to read just enough Swedish that I could gain a competitive advantage. And it paid off. I had a platform and an audience, people respected my opinion, and I was able to have enjoyable dialogues with people all over the world, including an unnamed future NHL Hall of Famer who is currently winding down his career. This was peak Dan.4

I began ruminating on this a little while ago when I stumbled into an article about hockey prospects on The Athletic. This thing had over a thousand comments! When I was writing, getting that many views was considered a win. Perhaps unsurprisingly, most of them were completely unhinged. A lot of stuff in the “how dare you?” or “you’ve lost all credibility because you disagree with my opinion” vein of thought. The level of vitriol being spewed on the topic of the future development of teenagers was so toxic I could only imagine the author wanting to escape the comments worse than that guy in 127 Hours wanted to get out from the rocks, potential amputation and all. This was a far cry from the internet hockey prospect community I knew and loved. Why?

Look at that terribly low level of information I detailed. We had almost nothing. Now, we aren’t relying on local papers and college message boards and poorly translated Swedish. If I search for “[insert team] top prospects” I get endless pages of results, up to the minute stats, dozens of scouting reports, even actual video of the players that isn’t a VHS taping over Babylon 5 episodes. This is a quantitative change in information. But is it really qualitative?

Not really. Remember, multimillion dollar corporations (NHL teams) employ teams of seasoned scouts more wily and grizzled than Rooster Cogburn working on this and they do a pretty terrible job of anticipating what will happen. They have huge analytics departments filled with brilliant Dartmouth and CIT grads who are also doing a terrible job anticipating what will happen. Very smart people have tried very hard in much more quantifiable sports, to limited avail.5 Why? Because figuring out the development of a teenager is really difficult! No one can do it well. Think about how the average professional investor generally doesn’t even beat the market. It’s because that’s really hard!

So what happened was that 20 years ago we had very little information but we knew we had very little information. We were as confused as a drunk person trying to watch Inception for the first time, but at least we knew it. Now, we have lots of information, but what we don’t have is the understanding that it’s not providing a significant upgrade to our accuracy. It’s providing a significant upgrade to our confidence. And if there’s one thing the internet in general, and social media in particular, is amazing at, it’s providing information. We have a veritable repository of all human knowledge in our pockets no idea how to use that.

The stakes are low with hockey prospects but what about when they’re high? Starting around the time Tom Hanks tested positive and the NBA shutdown, we went from having a trickle of information into a nonstop flood of coronavirus information. The problem was, most of that information was pretty useless. We could spend hours just reading COVID horror stories. But the actual what and how of the virus was still largely unknown. If you go back and look at mid-March 2020 it looks as bizarre as that brief period after Black Swan when we all thought Mila Kunis was going to be the next great dramatic actor. We thought we could beat this thing with Lysol wipes and t-shirts tied around our face. But we had enough information that, in the span of weeks, people developed entrenched positions about the virus. For many people, those positions have never changed.

Yet, even after all this time and all this information flooding us we’re still hilariously uninformed. Look at how wildly wrong Americans are on issues of likelihood of hospitalization and chances of death.6 And yet, think about how strong people’s opinions are, all rooted in certainty.

Because we live in a democratic system of government this has serious consequences. Do lockdowns work? That’s a complicated question. This Scott Alexander post on the effectiveness of lockdowns is probably the best I’ve read, and it is an incredibly smart person interpreting a lot of data. And not to spoil it – because if you’re interested it’s worth the read – but it’s all rather unclear. There are some interventions that probably do work, and there’s some interventions that either don’t work or are not worth the cost. Does masking work? Is outdoor masking useful? There’s a lot of people with very strong opinions on these issues. Think of the terabytes of heated debate solely over the issue of masking children in school.7 Because of that we have many places (choose your own adventure) forcing people to wear masks when it serves no benefit/not having life-saving mask mandates and causing this virus to keep spreading. How is it possible to have this much certainty on this unclear an issue?

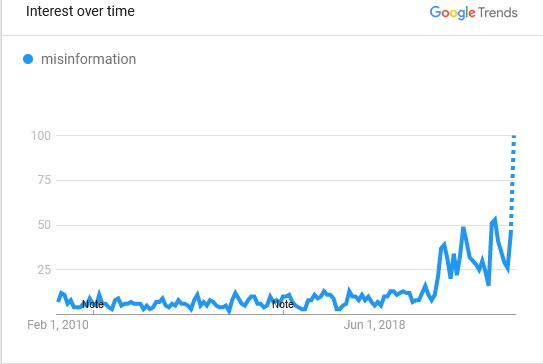

Some claim the problem is misinformation. People love talking about it, particularly over the last few years. That’s not an exaggeration.

That’s a massive uptick in talking about misinformation. But, with both the angry hockey nerds and COVID-19 deniers/alarmists, we’ve talked about people being very certain in opinions and you can assume some of these people are very wrong. But we haven’t talked at all about people having wrong information. What if the problem isn’t misinformation? What if the problem is that we just have too much information? What if we’ve worked ourselves into a situation where confirmation bias is just running wild?

Let’s suppose that a news site serves you a story about an elderly, vaccinated, immunocompromised person – perhaps a retired general – who dies after contracting COVID-19. And let’s say that the story is true, and that the story is not even written in the popular quasi-editorial story so many news stories are. What does that do to you?

Well, if you think COVID isn’t that big of a deal, you have a story confirming your beliefs that the vaccine doesn’t work, that it’s mainly old people who die from this, and that there’s a lot more “dying with COVID” than “dying from COVID.”

But if you’re one of the people who is really into COVID being the biggest issue in your world? You read a story confirming your beliefs that COVID is a deadly killer, that we need to protect the vulnerable, and that the unvaccinated are essentially murderers.

It’s entirely possible that’s one of those positions is completely accurate and one is as dumb as giving a Best Picture award to The King’s Speech. The point is that you can read this story and use it to confirm your beliefs no matter what your beliefs are. And now, we can serve you dozens of stories like this every day. And if they’re true, they’re not misinformation. But they’re just making you more certain in your, possibly wrong, beliefs.

I am not the first person on the internet to complain about confirmation bias. What I’m arguing is that confirmation bias combined with an uptick in information orders of magnitude larger than humanity has ever had is a dangerous problem. Misinformation is more comforting devil. You just need experts to proclaim the truth and then keep the lies from spreading, through removing misinformation and those who spread misinformation. And, like most comforting devils, its comfort is part of the allure in believing it’s true. But if accurate information can help people become more certain in wrong opinions, how do you fix that? Now we’ve moved away from “provide people with true information and they’ll have right opinions” to “we need to make sure people draw the right opinions from the same information.” If I’m right – which I may not be! – we’ve gone from a distressing but solvable situation to something more depressing than the end of Toy Story 3.

In a land of misinformation, we can fight it with facts. But in a land of too much information, facts may not help. Here’s some facts for you. According to the CDC website, people under 18 have a COVID death rate of 0.9 per 100,000, which rises to 43.7 for 18-49, 253.5 for 50-64, and 1,296.5 for seniors. Those are facts.

But what does those being facts matter? If you’ve decided COVID-19 is overblown those just reinforce the belief that COVID is just a problem for the elderly and that’s probably overcounting due to the from/with issue. If you’ve decided COVID-19 is an existential threat those reinforce their belief that this is incredibly deadly for certain groups and that’s probably undercounting excess mortality. Those facts don’t fix our issue.

This isn’t just COVID-19. You can easily find out the answer for how many unarmed Black men police shoot every year.8 But every political group gets this number wrong, with some laughable results. You can easily find out what percentage of the federal budget America spends on foreign aid.9 But if you ask people, they think we’re spending a quarter of our tax dollars on this.10 It’s obvious that these are two topics where the level of outrage about them leads people to have wrong factual beliefs, even if they haven’t been given wrong facts. Is that misinformation? Should people only talk about things in proportionate amount and intensity to the actual problem?

If I was smarter, this is the part where I’d bust out some amazing solution and become rich and famous. If I was dumber, this is the part where I’d recommend some ineffective solution with horrific unintended consequences. But I’m smart enough to know how dumb I am, so instead, I’ll have neither. Because the problem is not going away and there probably isn’t a good solution. It’s amazing I’ve written 3,000 words about information and misinformation and the internet and COVID-19 and haven’t mentioned Joe Rogan and Spotify.11 The main reason for that is because the issue of bad medical information on the internet is an old one. This journal article about the perils of the explosion of information on the internet has a part I want to quote at length:

Given the ease of electronic publishing, many within the medical community are concerned about the validity, quality, and consistency of medical information on the Internet. As important as the quality of information is, we must not overlook the implications of the quantity of information. Classic informatics theory shows that as information increases, the amount of irrelevant and inaccurate information (often referred to as "noise") also increases. Therefore, as more information is placed on the Internet, the probability of a patient finding relevant and accurate information decreases. This paradox of information theory has led one analyst of the Internet to comment that when "there is noise and someone assumes that there isn't any, this leads to all kinds of confusing philosophies."

That sounds about as dead on accurate a way of describing the problem as I’ve heard. But here’s the thing: that article is from 1998. It was talking about the growth of internet users from three million to 80 million. We’re about to hit five billion. This is about as dead on a prediction as saying Jennifer Lawrence was going to be a megastar after Winter’s Bone.12 This is almost a quarter century of discussion over this issue. We aren’t solving this problem, probably ever.

That quote does touch on something very important though: knowing there’s noise. Those angry hockey nerds aren’t watching deep fake YouTube clips or looking at doctored player stats. They’re consuming true information and thinking it means more than it does. We’ve been desperately trying to find technical or legal solutions to these problems. But maybe what we need is a cultural solution. Maybe the solution is that we all just accept that we don’t know as much as we think we do?

My third favorite Fincher film, behind the criminally underrated Zodiac and the grossly underrated Gone Girl. I should make this piece about how David Fincher’s 20th Century movies are overrated and 21st Century movies are underrated, but I can’t find a tech angle.

I find some of the native social media critiques very compelling, namely, the issues that arise from the algorithms. But that’s a different topic I’ve already discussed.

As a quick note, I will not, under any circumstances, touch on the issues of whether these places should be allowed to spread false information. This touches too closely on legal issues, and, hey, analyzing legal issues is my day job.

It was also Archetypal Dan, as I abandoned this when I went off to college. In 1998. Right before an explosion in both popularity for niche sites like the ones I wrote for and corporate buying sprees. The sight I mainly wrote for became huge (in the hockey world) for a while, with numerous former colleagues now doing this professionally. Another site I wrote for got bought by NBC and the other writers became professional, credentialed NHL journalists. One of my friends and colleagues has been doing it for 20 years and now even works for the team! But, I mean, I go into the rewarding career of… being a lawyer.

There’s a very famous book about this, it’s called Moneyball, they made a movie starring Brad Pitt.

Both of those stories are interesting because they’re from competing camps and attempt to portray the results as favorable to “their side” while the numbers still show that people are bad at estimating these things.

This is interesting enough to merit a footnote because it shows the oddity of tribalism. To steal terminology from the just referenced Scott Alexander, masking kids in school falls neatly among the blue tribe/red tribe divide here in America. Yet, the Nordic Countries, which are about as blue tribe as it gets, take the outlook that – much like in that Who song and the Mark Ruffalo movie – the kids are all right. The risk of COVID-19 to children mirrors people’s views on the welfare state within our country, but not outside it. What does that tell you?

It’s estimated to be between 13-27 in the last pre-pandemic year. Although, FYI, if you google this expect a lot of headlines that inflate this number and then say “since 2015.”

1%, which most people believe should be “cut” to 10%.

I want to defend my fellow Americans from the normal “haha, Americans are dumb.” On immigration at least, Americans are as misinformed as Europeans, even the vaunted Swedes.

Partly because I wrote most of this article before my two-month climate change odyssey and didn’t want to rewrite the entire thing to frame it around my fifth favorite Newsradio cast member.

Once I realized I was referencing both The Social Network and Moneyball I decided to see if I could fit in all the Best Picture nominees from that year. And with that one, mission accomplished!

Really enjoying going through your archive and this article is a delight (and wildly relevant), but about Footnote #1 - super going to need a long form article about David Fincher's movies and your rankings because oh my god, why isn't he the director version of Meryl Streep at the award's ceremonies? I have a complete lack of understanding why Gone Girl isn't at the forefront of every list of how to make a thriller and it really floors me when people have no idea what show I'm referencing when I say, " Mindhunter".

Now I’m trying to figure out who the four cast members are that you’d put ahead of Rogan. I feel like Dave Foley, Phil Hartman, and Stephen Root are gimmes, so I’ll say the fourth is… Vicki Lewis? It would be for me. I think Beth is often unsung but vitally important in the ensemble.