Twilight of the Cinematic Gods

Or, What Apes Teach us About Platform Decay, Creative Destruction, and the Mushy Middle

When last we spoke1 I talked about a problem known as “platform decay” which has the more internety title of “enshittification.” The idea of making products or services worse – from a customer perspective – to increase profits is a popular one. But today, in my longest piece ever – feel free to read it in shifts, I won’t be offended – I’m going to take that concept and two other concepts – the mushy middle and creative destruction – and spin them together to tell a tale. It is, in fact, a tale about the death of telling tales. It’s a tale about the death of the movie theater.

Last Friday night, after a very long week, I decided it was time to finally go and see Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (spoilery review in the footnote).2 I’ve been an Apes movie fan since I first saw the original and enjoyed all four sequels. I adore the reboot trilogy and think it’s an incredibly underrated piece of 2010s filmmaking, with more quality in the writing, acting, and CGI than it gets credit for. I even like the bad Tim Burton remake even if it is objectively quite poor. Which means I was excited for this. But at the end of I walked out not with excitement but with a lesson. No, it wasn’t apes together strong, because I already knew that. I live my life by that. It was the lesson that industries whose reaction to technological change is enshittification are signing their own death warrant.

Movie theaters are having a rough go of it. This topic is the most “it’s so over/we’re so back” of topics. Something like Barbenheimer happens and the movies are fine. Then another Disney movie flops and we’re asking why movies are dying. Then Dune 2 does great and we’re back, then The Fall Guy and Furiosa flop and everyone is asking why movies are dying. Now that Will Smith reminded everyone what a movie star looks like, I’m sure this piece is untimely, but I guarantee we’ll be discussing this again in a few weeks. And, adjusted for inflation, movie box offices are down. A lot. Even pre-Covid they were down. So why?

I’ve written before about creative destruction, which is so entangled with the very idea of technological progress that it’s difficult to not repeatedly return to. And movies are a great example of this. The movies themselves were their own form of creative destruction. For as long as civilization has existed – and likely before then – we’ve had an insatiable appetite for stories. And watching them play out has been an eternal pastime. There’s a reason that as a theatre arts major many of my courses began with the Greeks. Theatre, in whatever form it was presented, was always a popular activity. Despite its current status as an elitist activity, it was also for the masses. Until movies came.

For the entire life of the movies, it has been nothing but creative destruction. I don’t think Babylon is a great film – it needs an editor badly – but it does have one my favorite scenes in recent years, when the main character sees a “talkie” for the first time.

Sound motion pictures completely destroyed the silent movies. The transition was not as smooth as from black and white to color, it was violent and disruptive, just like creative destruction always is. It also gave birth to everything from Classic Hollywood to Italian Neo-Realism to the French New Wave and on and on, for which we are all glad.

But for the frist half of the 20th Century, when the killer of creative destruction visited itself upon cinema, the call was coming from inside the house. That changed with the invention of my best friend, television. For the first time ever, people who were not royalty could watch stories from the comfort of their own home! In my last piece I talked about how this radically changed sports. It didn’t radically change movies, at least not right away. But television was seen as a rival to the movies. Which meant there had to be a differentiator, and that differentiator was quality. Movies shown on television were usually older, not shown in regularity, and shown on a far, far, far, far inferior screen. And movies made specifically for television were just not as good. There’s a reason so few of what came to be known as “made for TV movies” are remembered. The big screen was where you went for quality. This wasn’t people eschewing the Louisville Redbirds because they could watch the far superior St. Louis Cardinals. So, unlike minor league baseball, movies didn’t just survive, they thrived.

And then along came home video. When we talk about home video, we always talk about Netflix creatively destroying Blockbuster. I’ve talked about it endless times myself. We don’t talk about how revolutionary home video itself was. Part of why Gone With the Wind has the best box office numbers of all time is because it was getting re-released regularly, which was the only way to see it except perhaps a special showing on television. Home video said “no more, friends, you can watch this movie whenever you want.” And movie theaters hated home video. Which is in part why the studios put such a long wait on when a movie could be released to home video and when it could be released to television.

A great example of this is Jurassic Park. I am not a nostalgia guy. I loathe nostalgia. I assure you that I say this with no nostalgia: it’s the greatest blockbuster of all time. It is, to me, exactly what movies should be. This never could have been done on a stage. It had to be a movie because only movies can create this level of magic. Look at that scene below, this is using film making technology to create images out of our wildest fantasies within the confines of a compelling story. It’s a masterpiece. Which is in part why when it first came out in theaters it did numbers. No film before it ever made $50 million in one weekend. It’s estimated in its theatrical run it sold over 80 million tickets. Almost as big of a deal was its release to home video. Where, despite having been seen by so many people already, it still became the fifth best-selling VHS tape ever. The truly remarkable thing is its television debut. For context, last year, the most watched television broadcast in America was the excretable filth that was the “Super” Bowl, which garnered about 115 million viewers. The next highest was another terrible American football game, which got about 53 million viewers. When Jurassic Park was first shown on television, it was watched by 68 million Americans. This was the model working to perfection.

Much – I’d argue most – is due to quality. But that’s not the only element, even if it is the key one. Because for those of you who don’t remember this, let me provide you with three facts. After being released in June 1993, it did not get released on VHS until October 1994. It did not get put on television until May 1995. Finally, the average American television in 1995 looked like this:

In case you didn’t see where I was going with this, that picture should make it clear, roundabout pun intended. Movie theaters were a product of their technological day. First, destroying live theater as mass entertainment. Second, surviving alongside television and home video because quality was better. And third, what it is now. Which is the mushy middle. But before we talk more about why that’s bad, let’s turn back to the question of why fewer people are going to the movies.

There are a lot of opinions on this, and most of those opinions are right. This is a multifaceted problem. But this is not a multifaceted newsletter. It exists to do two things: talk about technology and make Elder Millenial pop culture references, and we’re all out of Elder Millenial pop culture references.3 And I believe the biggest issue is a simple one: technological change.

Simply put, being able to watch a movie at home is just too easy (because of business choices) and too good (because of technological advances) for movie theaters to compete. Even if you think the quality of movies is as good as it was 20 or 30 years ago, the quality of watching them in the theater versus watching literally anything else at home is much smaller.

I wrote once – and I’m not linking to it because it needs to be rewritten – about how quantitative changes can lead to qualitative ones. That’s what happened with televisions. I have a friend who doesn’t go to the movies because he has a home theater. And I like his home theater. But it’s nowhere near as good as a movie theater. It is, however, so superior to the televisions of the 20th Century that it is not even the same thing anymore. There was a qualitative change, meaning we went from only being able to watch movies in the theater, to only being able to watch quality movies in the theater, to only being able to watch quality movies in the theater or on a vastly inferior device, to being able to watch quality movies at home on an excellent screen almost immediately after they’re released in theaters. This seems important in explaining what happened!

The combination of streaming services and improved televisions are killing movie theaters, just like movie theaters once killed popular theater. But recall, they didn’t totally kill theater. It may be more of a Frasier in Frasier activity than a Frasier in Cheers activity, but it still exists. It became a niche product with a different value proposition, appealing to a different base. We’ll come back to this, because first, we need to return to enshittification.4 And my trip to the movies.

I picked a 10:10 show on a Friday night, arriving at 10 o’clock to have enough time to buy my ticket and some snacks. I purchased one ticket, one medium sized popcorn, and one of those small Gatorades. I paid $31. I then ambled into the theater at 10:08 assuming I timed this perfectly. I did not. There were then over 20 minutes of commercials. Not previews, which I – and most moviegoers – enjoy. Commercials. By the third straight commercial for a soda I lost it. I didn’t leave the movie theater until 1:20 in the morning.

There’s a lot of problems here. The first are concessions. One thing minor league sports do is have more reasonably priced concessions than major league sports. This is for the obvious purpose that it makes them more attractive, particularly to families. The tickets themselves are also less expensive, again for obvious purposes. But they’ll make more money off me by marking up that Gatorade four times what I’d pay at a convenience store, so they do.

You know what I, like most people, hate? Watching commercials. And although no one wants to watch them, at some point movie theaters realized they could play them between showings. You gotta have something on the screen, so why not that if it makes some more money? But every time I go to the theater it is increasingly longer and longer stretches of commercials. This does not build customer satisfaction, which also delays the movie start time (because people know to not show up when the commercials are playing).

Now, these may seem like minor complaints. Don’t buy snacks at the theater! Oh no, you had to watch commercials? Oh no, you had to spend over three hours there? Poor you. It’s part of the insidious nature of the “first world problems” meme. Yes, these are problems. They suck. Whether or not I will survive is irrelevant. Whether or not they enhance my experience is what matters. Because it’s a business! Do you know why customer service businesses tend to frown on their employees cursing out customers? Because they want you to come back and that means you must like the value proposition.

Meanwhile, the value proposition with movie theaters has over the course of my life gotten progressively worse.5 Partly because of everything I talked about before. On the one hand, I can choose to watch a good movie shortly after release at any time I want in the comfort of my own home for practically free on a screen that delivers a first-rate viewing experience. On the other hand is what actually exists, which is seeing the movie slightly sooner on a bigger screen while being squeezed out of every penny the movie theater can squeeze out of you. Because they can’t think of any other way to make profits. This is enshittification in the real world, it’s terrible, and it’s part of why people keep choosing to not go to the movies.

All hope is not lost. There are three options, the first of which is in the hands of the studios. It’s to try and made the other option – watching it at home – worse. Which they can’t do because they don’t own the television companies. But they do own the streaming studios. Instead of flushing billions down the drain of the economically unviable streaming fad, they could go back to have longer exclusive windows for theaters. Try and rebuild movies as events. This seems unlikely to occur, because movie studios that own streaming services have entered sunk cost fallacy territory and the ones that don’t can’t say no to that streaming service cash. Which leaves two options, but before we discuss those, let’s talk about the mushy middle.

A few weeks ago I had a conversation with a very smart person, the type of conversation that leaves many intellectual trails to go down. One phrase she used – in a completely different context – was about the mushy middle. I couldn’t stop thinking about the mushy middle because I realized that I hate it. In everything. This is not an argument against moderation, but against half-assery. I often say I drive a Honda because I can’t afford a Ferrari. If I had the money for a truly elite status symbol of a car, I would spend it. But if I don’t – and I don’t! – I’m going to spend my money on something reliable. Most people disagree with me, and I don’t want to insult BMW owners, so let me pivot to a different analogy, one that is apt for discussing movie theaters.

When I choose to play golf, I usually think of three options. The first is my favorite, which are cheap municipal courses. Are they well maintained? Usually not. The amenities aren’t as nice, the course design and layout may not be as good. But they’re inexpensive and fun. Alternatively, I like the idea of truly top-notch courses. Last year we played one that was just used for U.S. Open Qualifying and the quality of that course – in every manner possible – was excellent.

What I hate playing are the mushy middle courses. You golfers know the ones. They’re $80-100 a round. They have a nice layout, maybe a signature hole or two. They’re better maintained than a municipal course, but nowhere near the quality of the best courses. They’ll have some amenities. They stand between the high end and low end, offering a slightly better experience than the latter at a far greater price. And I have no interest in them. Either give me cheap fun or expensive excellence. Don’t give me moderately priced okayness. Rubbish to the mushy middle.

But that is exactly what movie theaters are. Just expensive enough to be annoying, not nice enough to be a truly good time. Which is why – like live theater – they have the option to pivot to the high end. Embrace being a niche and make it a classier experience. Part of why I go to (not as much as I’d like) the theatre is that it’s not just an overall enjoyable experience. It’s also formal, and I, like baby Jesus in a tuxedo T-shirt, likes to be formal, but also party.

This is the approach taken by companies like Alamo Drafthouse, which seemed like it was doing quite well before the pandemic. Offering servers with alcoholic drinks and full meals. It’s more expensive but it’s a much nicer experience – at least most people think6 - and offers a value proposition different from the home movie experience. Yes, you’re going to pay more, but it’s like going to a bar or restaurant, you just get to watch a movie.

The final option is also to pivot, but this time, pivot the way minor league baseball did. Movies have always been a mass appeal business, even during the heights of the Depression it was considered something people could go and do. I’m a single guy who’s not particularly indulgent and I spent $30. I can’t imagine what it’s like for families. Turn movies back into their mass appeal roots.

This idea is not as ridiculous at it seems. The reaction theaters have had to the growth of at home options is always the same: raise prices. If you look at 2002 (when DVDs were popular and HDTV was just taking off) the domestic box was – adjusted for inflation – almost $17 billion. Last year it was almost $9 billion. Even in 2019 before COVID – a year that a Star Wars and Avengers movie came out – the box office was only $13.2 billion, slightly more than what it was in 1995 when the highest grossing film was Batman Forever. But that year the inflation adjusted average ticket price was still about 25% cheaper than in 2019.

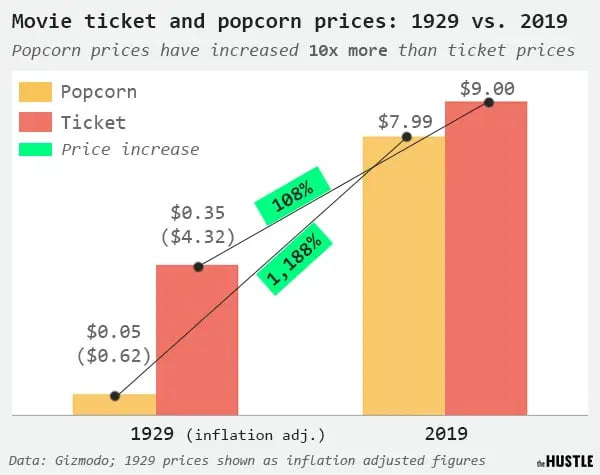

The concessions are even more ridiculous. Yes, an 800% markup is fine and all. And, in the defense of theaters, perhaps would not be necessary if movie studios let theaters keep more of their ticket sales. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find prices from my youth, and don’t wish you to rely on my memory. But I did find an interesting article that contrasted prices from 1929 until 2019, which I think is interesting in driving home my thoughts on movies as a working class activity. In 1929 you could go to the movies and buy a popcorn for about $5 in 2019 dollars ($6 today). In 2019 it was $17. Yes, movie tickets doubled, but the popcorn is where the big increase came. The quality of your competition is increasing, so your response is to raise prices. Yes, you’ll squeeze more money out of the people who still go, but you are going to lose people.

Worse, you are inhabiting the mushy middle. You’re not a fancy, high value experience. But they’re also not an inexpensive fun time. All you can think to do is to try and lower your customers’ enjoyment level in small ways to squeeze out every last penny. And I get it, I sympathize, it’s the middle class trap all over again. If you pivot your business you risk dying quickly and spectacularly. Instead, you can just bleed out slowly, hoping something comes along and saves you.

But that won’t happen. Nothing will save you. Televisions are not going to get worse, they’re going to get better. And people who have the disposable income for $30 trips to the movies are more likely to have the disposable income for truly impressive screens or virtual reality headsets. You’re not going to appeal enough to the people who can afford you while pricing out those who you could appeal to. Which means you’re left with either a creative renaissance beyond our wildest imagination, making going to the movies a core part of human desire, or you’re going to bleed out and die. You’re going to bleed out and die.

That’s why I don’t mind saying this article is about the death of the movie theaters. Their necrotic corpses will continue perambulating for years to come, but they’re dead. They will someday survive as niche products, much as I could go to a drive-in movie theater now, or to the theater, or see a symphony, or find someone reciting poem like they’re Homer. They will never completely cease to exist. We are story consuming machines, and we’ll always have enough people who like consuming stories in a certain type of way that it’ll be there. But the days of movie theaters as mass entertainment? Forget it Jake, it’s Chinatown.

Look, I just need to accept these articles won’t be regular. Bye bye popularity! But when I have something to say I’ll publish it, it’s not like y’all pay me.

Twas good, nowhere near as good as the Caesar trilogy. Felt more like setting up a sequel. But opening the movie with Caesar’s funeral evoked emotions in me I didn’t know I still had.

That’s a lie, we’ll never be out of those. I’m slinging those around like they’re pogs.

I prefer the term platform decay to avoid cursing, but the problem is this is just a much better term because even if it was coined for online platforms, it can be applied broadly.

I would hope that despite my earlier comment on my hatred of nostalgia and also the fact that I write a newsletter dedicated to evangelizing progress, I don’t need to explain that “no, I’m not the kind of guy who thinks things were better as a kid.”

I had friends who insisted in seeing movies at the Drafthouse, including the one I would go see the MCU films with. Which meant when I saw Infinity War with him, it was in a Drafthouse. It was also brutally hot. And the guy next to me was both a loud eater and ordered the most pungent smelling wings. Sitting there next to him, listening to him eat, smelling these awful things for hours. Kinda ruined the experience for me.

I never fully (fully) realised that the American word for cinema is theater, the SAME word used for actual theatre. I mean I did know of course but it never sunk in.

I think the lost mushy middle framework applies particularly to entertainment and other optional goods and your point that most people who can afford cinema tickets can (or soon will be) able to afford home cinema kit. Isn't this whole thing partially what drives the 3D craziness?

Also, I will maintain forever that food in cinema (apart from something quiet and odourless, PERHAPS) is barbaric but I get that I'm a weirdo snob. WINGS????? Cmon.....

I saw "The Fall Guy" in a theater during the second weekend of its release. A couple days later, the movie was available on VOD — for the same price my husband & I paid for our two Sunday matinee tickets. (If we'd gone to an evening showing, VOD would have been considerably cheaper.) Honestly, why bother seeing anything in the theater if it may be available to stream mere days later?