I’ve previously trumpeted my micro-generation – the Oregon Trailers, to use my favorite name for us – as having some sort of unique perspective on the digital revolution. Like all generational discourse, it’s mostly nonsense. Sure, it’s basically true for our internet usage, but there’s many parts of the world today that are as alien to us as Spotify is to my mom. Including online dating.

Sorry to disappoint, but this will not be a collection of my own embarrassing Tinder stories (although I expect you to share yours in the comments).1 For everyone I know my age who is fluent in Bumble, there are three who find themself baffled. That’s because while things like texting, online shopping, and social media were all instant hits, online dating was decidedly not.

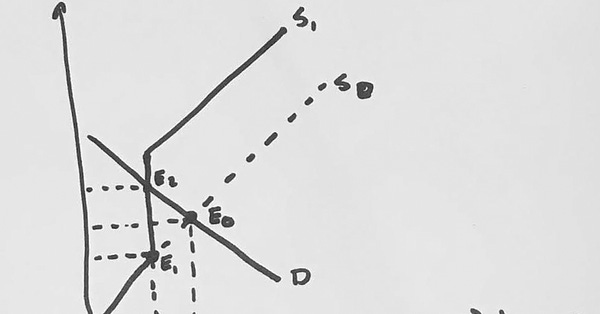

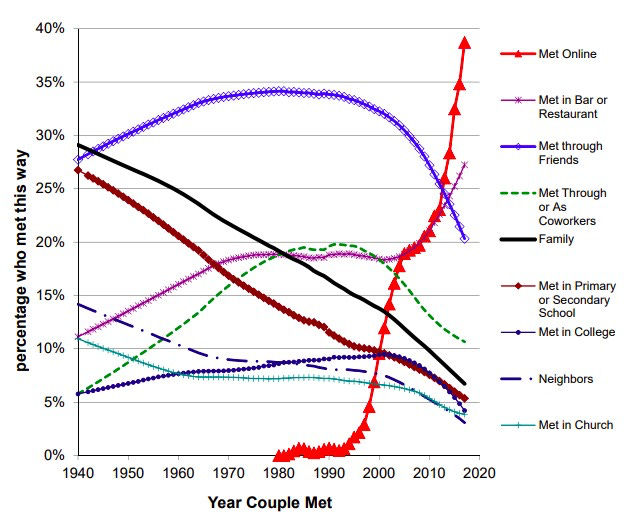

In the 90s, meeting someone online was highly stigmatized. That stigma carried through into most of the next decade.2 But as we can see, that growth rate is astonishing. Not only did meeting online become incredibly popular incredibly fast, it’s now more popular than any other method has ever been in the eighty years on that chart. Within the span of one generation, it went from a stigmatized eccentricity to the expected way to date. After all those weeks of talking about failed disruption, well, this is what disruption looks like.

But if this is the de rigueur way of meeting someone, is that actually good?3 The differences between online dating and analog dating are fascinating and would make a good article. And it did. I don’t want to link to an article then write a worse version of it. Instead, I’ll note that despite some disagreements that Atlantic article nails the basic idea that for all the complaints about online dating, analog dating was just as bad. For some people it was quite worse. Instead, let’s take a step back and ask if the Tinderization4 of dating is good not for the individual daters, but for society.

Dating is a relatively new innovation. Prior to the last couple of centuries, marriages were arranged – as they still are in some cultures. The invention of dating was, like the mullet, a brilliant combination of business and pleasure. Traditionally, marriage was mainly a business arrangement. Coupling allowed for marriage, itself a property arrangement – ask any divorce lawyer – and having children, which had both an economic component and the happy side effect of perpetuating our species. Then along came dating to combine this with romance. In addition to being the basis for most of our music, art, and unnecessary television plotlines, romance is also a potential source of that important but ephemeral thing known as happiness. Theoretically if online dating was doing its job for society, it would improve happiness while also facilitating marriage and childbirth. Is it?

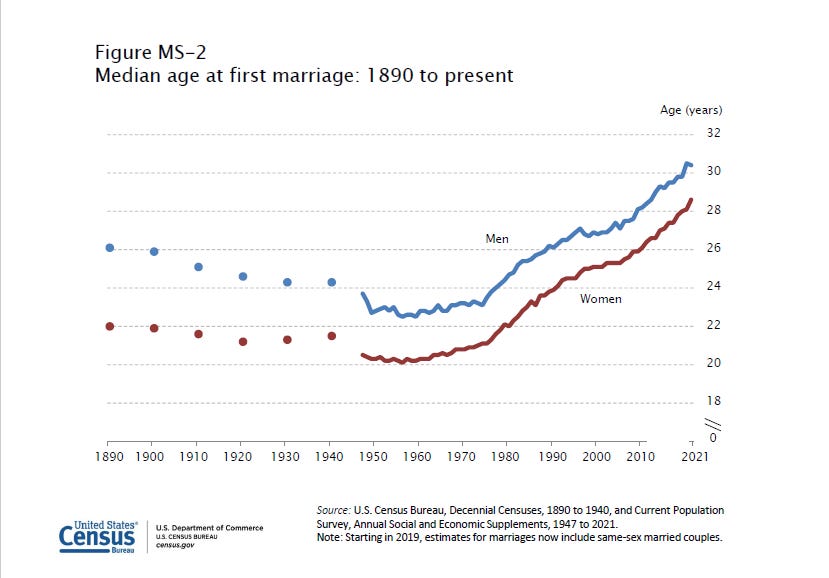

The latter two are a bit more difficult to address because its widespread use is so new. This article could age as poorly as one of my NBA takes.5 We may look back at the boom in happy marriages and rising birthrates and have a national Tinder Appreciation Day. But so far, it doesn’t look promising. What we know is that people in the United States are getting married less and later.

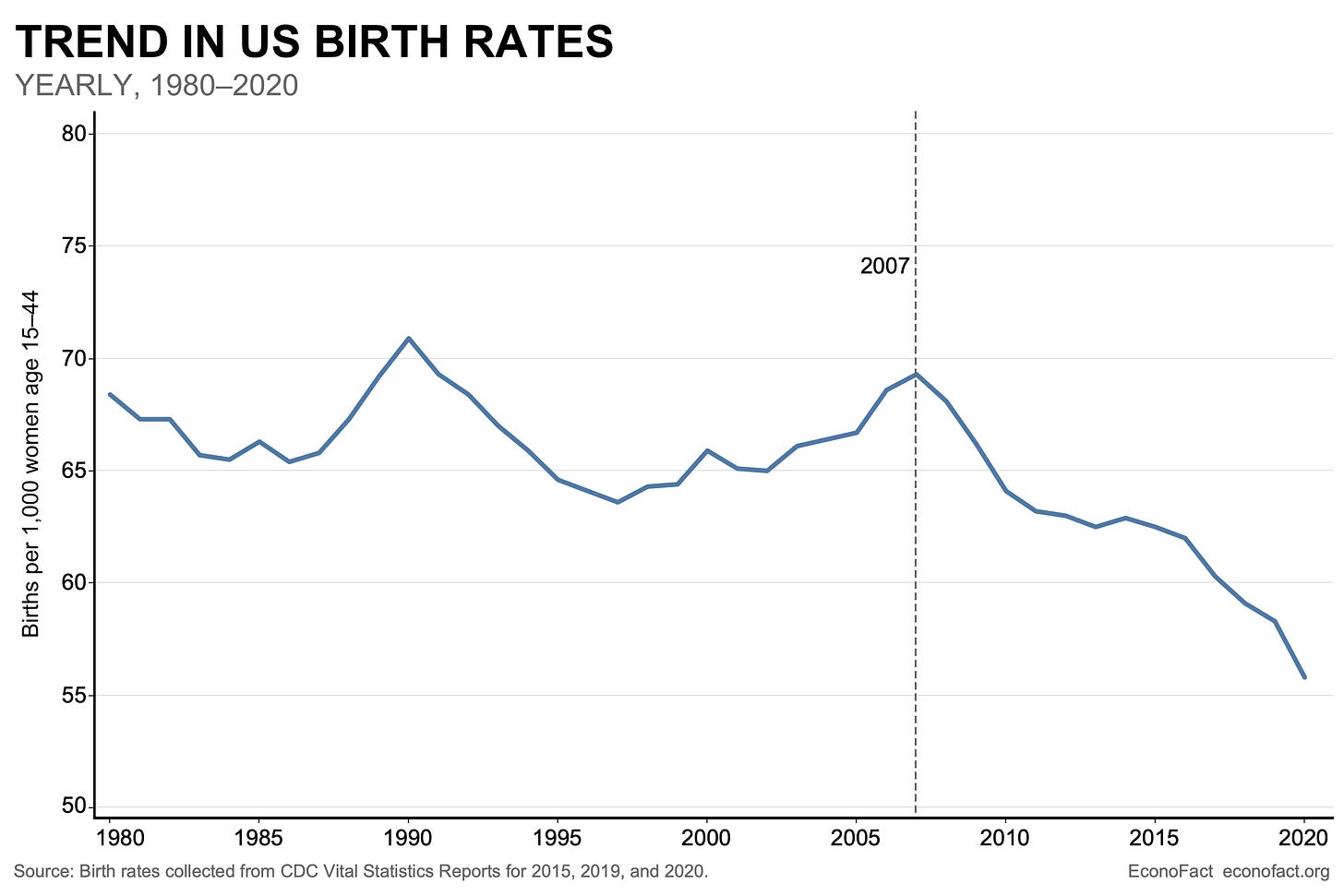

We also know that people in the United States are having less children.

The reasons for these phenomena are many and it would be absurd to blame this on Match.com. But as this becomes the dominant form of coupling, it is doing nothing to arrest these declines.

As for our second question: does online dating make people happy? The answer very much depends on who you are and what you’re looking for. There are two ways of looking at this. First, is that we managed to take dating – something that is inherently unequal – and in true 21st Century style ramp up the level of inequality. You may already be familiar with the numbers on this, but basically:

Essentially, all these apps create dating economies with massive levels of inequality. This isn’t surprising. We don’t know a lot about the algorithms but when Tinder let their previous algorithm be examined it was essentially an ELO rating. If you want people to keep using your app, you’re going to present to them the people with the broadest physical desirability. Even if a car dealership knows you’re going to buy a Honda – which is a superior vehicle – it’s still going to put the Mustang in the most visible place. If you’re out there wondering why these apps don’t work for you – especially if you’re a dude – it’s like someone born in South Africa wondering why they’re not rich. It’s probably not you, it’s just setup that way.

There’s a more fundamental problem with online dating and happiness. It’s a problem that plagues most of the internet with its functionally infinite storage capacity: the paradox of choice. For those unfamiliar with this concept the most basic version is that having a lot of choices leads to humans being more stressed and dissatisfied with our choices. Thirty years ago – on his eighth best album – The Boss sang about there being 57 channels and nothing on. Today we have twice that plus endless streaming options and lots of people still inexplicably choose to rewatch The Office. Well, Bruce was wrong,6 there was a lot on. It’s just the act of choosing itself makes us unhappy. But unlike endlessly scrolling through Hulu for something to watch, Doordash for something to eat, or Amazon for a new blender, it’s scrolling through dozens of people for someone to date. There’s always the possibility of someone better being just one swipe away. It’s a FOMO nightmare. As counterintuitive as it is, the very design of online dating apps is ideal for maximizing anxiety and dissatisfaction.

But I think if we take one more step back the problem with online dating becomes even more fundamental. In the pre-dating days, coupling was arranged mainly by parents whose goal was to maximize the business part of this arrangement. Then dating came along and we gave way to no one having a hand on the wheel. Look at that list of sources: bars, schools, and offices all have one thing in common: they’re not trying to set people up. Dating was in the hands of randomness, with all its brutality and beauty. Once we moved to online dating, we put coupling into the hands of a for-profit venture.

Online dating services weren’t the first people to try and make money off matchmaking. Those services existed before and still do now. However, without the power of digital communications to create an economy of scale, they were niche services. Online dating is excellent at making money by the same way that anyone does anymore: subscriptions and microtransactions. The ideal user is someone just frustrated enough with the freemium version to upgrade but not so frustrated – or so successful – as to delete the app. It’s essentially the same as a casino rigging a slot machine to maximize near misses. There’s a hand on the wheel again, but is it the one we want?

To go back to our original question: is online dating good? It doesn’t look that way. We’ve turned the bulk of dating over to people who benefit from you not being too successful, exasperated inequality, and introduced a level of choice that makes us less satisfied. Not great.

So, what’s the solution? I’ve read the idea that a country worried about an incredibly low birth rate – such as South Korea or Japan – would be smart to foot the bill for an app specifically designed for people to meet, marry, and have children. I haven’t read what that app would look like, but this is a place for thinking big, so I’m certainly interested in that idea. But I’m not going to hold my breath waiting for a government to do something innovative, and I don’t see the effective altruists lining up to create a charitable version of Bumble. Since we’re probably not going to get a better dating app, let’s look for a different solution, and it goes back to the analogy I used earlier.

One of the best lessons of my childhood was when I first saw Atlantic City and was told to look at how grand the casinos are. Then I was told to wonder how they got that way. I love a good casino trip, but I know that they’re luxurious palaces because the people who walk in there lose. Even the best bets carry a house edge. Sure, some people win, just like some people get wonderful relationships out of dating apps. But if a dating app is really designed to be deleted, their CEO isn’t dropping $12 million on a house. You need to keep using their apps to keep the gravy train going. If that sounds fun – and it certainly does for some – then get swiping. Just realize that for everyone who walks out of the casino with money, ten more don’t. You’re paying for fun and the hope that you’ll be the one to hit the jackpot.

I started this by defending new technologies on the grounds that they’re not bad, it’s that our brains aren’t wired for them. Dating apps are the same. At worst, they’re taking a swing at a hard problem and doing nothing to make it better. They can be a lot of fun if you’re in the group they serve well and sucky if you’re not. But they’re not killing anyone. No one can use OkCupid to take down a country, although I’m sure Netflix will greenlight that movie if you pitch it – and I better get an executive producer credit in addition to the like, subscribe, and share. But what about the dangers of a technology that let people kill at ease with serious consequences to societal stability? Let’s ramp up the danger and talk about that on the next episode of Technopoptimist.

My experience with dating apps would be best described as limited but satisfactory.

I tried to find video of the How I Met Your Mother “there’s no stigma” “of course there’s a stigma, that’s why people say ‘there’s no stigma’” exchange about meeting online. But somehow this was impossible. I wonder if we overreacted in pretending this show never existed just because the last few seasons were so bad.

I’m going to note up front that this article is focused solely on heterosexual dating. This is for three reasons. The first is that it’s still much more common. Over half of all American adults are married or cohabitating with someone of the opposite sex, compared to 1% with the same sex. The second is that, even though this isn’t based on my own experiences, I still have some experience using these apps and a lot of experience dating and have put a lot of thought into this topic because it concerns me. I have never used Grindr and would be completely talking out of my ass. Finally, for obvious reasons, online dating is much more popular among same sex couples.

Footnote heavy this week as the response to my Netflix piece highlighted how sloppy I’ve gotten on addressing certain obvious points. I want to note that although I love that term, this isn’t all about Tinder. It’s merely the Kleenex of dating apps. The basic way all these apps work is similar enough I’m using them interchangeably.

Most of my NBA takes are gold. The long-lost episodes of the short lived basketball podcast I was on probably aged like fine wine. But I vowed eternal self-flagellation for telling everyone that the Magic were idiotic for drafting Dwight Howard over Emeka Okafor. It’s important to own bad predictions.

Of course, the song isn’t about nothing being on television, it’s a critique of consumerism. I would argue that the hollowness of consumerism is related to the paradox of choice, though, so let’s just go with it.

Aha! My favorite economic concept, the perverse incentive! The people who use the apps want to meet someone and stop using the app, while the app makers make their money by keeping users hooked. This is a brilliant insight! No wonder the apps are frustrating to so many users!

I highly recommend Seth Stephens-Davidowitz’s new book, Don’t Trust Your Gut: Using Data to Get What You Really Want in Life. He has a chapter on online dating, and he points to another problem with dating apps: The apps prioritize traits such as youth, beauty, and physique--which are precisely the least relevant traits for happiness in a committed relationship. For a committed relationship to be successful, you need emotional maturity, a sense of humor, and compatible personalities, all ineffable qualities that emerge organically when you meet someone irl, but that are invisible to these apps.

Plus, as my son could attest, people lie on the apps, which means that users don’t trust them. It’s well known that men on the apps have no chance if they’re shorter than 6’, so men who are in the ballpark of 6’ (say, 5’9” or above) will say they’re 6’ tall. My son happens to actually be 6’, and he says that the women he meets are always surprised to see that he is in fact the height he reported in his profile. I suspect that lots of women lie about their age and weight. This is another perverse incentive: If you have no chance to match on these apps unless you meet certain superficial criteria, why not lie about those criteria? But that incentive to lie degrades overall trust in the apps and worsens the experience for everyone.

Im sure that most people who met online met through a dating app, but I’d still be interested in seeing the number breakdown further to those who met on a dating-specific app and those who met just randomly on the internet. I myself met my husband the analog way, in college in 2000, which according to your graph was the absolute peak of meeting your spouse in college. But since then, although I too am a member of the Oregon Trail generation, I’ve made many good and lasting friends on the internet. Not on apps designed for that purpose, but on message boards or blogging and commenting forums like Substack. The idea of a dating app terrifies me, but I’m quite comfortable (and good at) making friends online in the random way that mirrors the randomness of real life meetings. I also know a couple getting married soon who met online, but not on a dating app. They met in a forum about a shared interest.