Empyrrhical Evidence

Down here it's just winners and losers and don't get caught on the wrong side of that line

Back in the 3rd Century B.C. the Roman Republic began the long process of subjugating the Greeks. The first such attempt was the Pyrrhic War, named after Pyrrhus, King of Epirus. Of course, you may recognize him as the namesake of something else. Pyrrhus managed to defeat the not yet invincible Roman legions at the Battle of Asculum. According to Plutarch, the armies of Pyrrhus were devastated, in men and commanders, while the Romans were able to immediately replenish their forces. Sadly, we had no intrepid journalists recording events for their Substack so we don’t know for certain what Pyrrhus said afterwards. But his words have come down through history as some variation of “another such victory and I am undone.”

Thus was born the Pyrrhic victory, the concept of losing by winning. Perhaps the most famous – and to my Gallic readers, painful – example is the Battle of Borodino, part of Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia. You may recall from history class or the Wikipedia article on War & Peace you skimmed so you can pretend you read the book. Yet, if this existed only in war it would be uninteresting. This concept translates to the world at large. Trust me, I’m a lawyer. Pyrrhic victories are our stock in trade.1

Perhaps the most common version is the Winner’s Curse. The overly simplified version is that in any auction whomever bids the most wins, yet, that means they most overvalued the asset. As such, they may suffer from that victory. The easiest example is in sports, where free agents (players out of contract) can result in bidding wars that are typically won by whomever pays the player the most. Yet, because American sports have wage constraints, the winning team can be precluded from spending money on other players. They then end up being worse off than the teams who lost the bidding.2 We see the same thing in overvaluing stocks, companies, or other assets. Defeat through victory.

As useful as this is, here’s the odd part: there is no widely accepted version of a term for the opposite of a Pyrrhic victory: winning by losing. Which brings us to the obscure topic I want to discuss: the ESPN Phone.

ALERT: THERE IS NO SPORTS CONTENT IN THIS ARTICLE - SPORTSPHOBES CAN CONTINUE READING

In late 2005, ESPN – The Worldwide Leader in Sports and a business juggernaut – launched Mobile ESPN on the Sanyo MVP. Commonly referred to as the ESPN phone, it was a cell phone featuring ESPN, including score updates, GameCast, articles, highlights, video, all created by ESPN’s industry leading content creators. Except, there’s a good chance you don’t remember it. If you need a refresher, here’s what $30 million of Super Bowl commercial got you back then.

Hey, people love sports and they love cell phones! Let’s combine them and we’ll make billions! Unfortunately, this did not work out quite that way. The definitive word on the ESPN Phone – taken from the brilliant These Guys Have All the Fun – come from the mouth of a man who knew a thing or two about cellphones, Steve Jobs.

The story goes that ESPN president George Bodenheimer attended the first Disney board meeting in Orlando, Florida, just after the company had bought Pixar, the innovative animation factory, and spotted Apple CEO Steve Jobs in a hallway. It seemed like a good time to introduce himself. “I am George Bodenheimer,” he said to Jobs. “I run ESPN.” Jobs just looked at him and said nothing other than “Your phone is the dumbest fucking idea I have ever heard,” then turned and walked away.

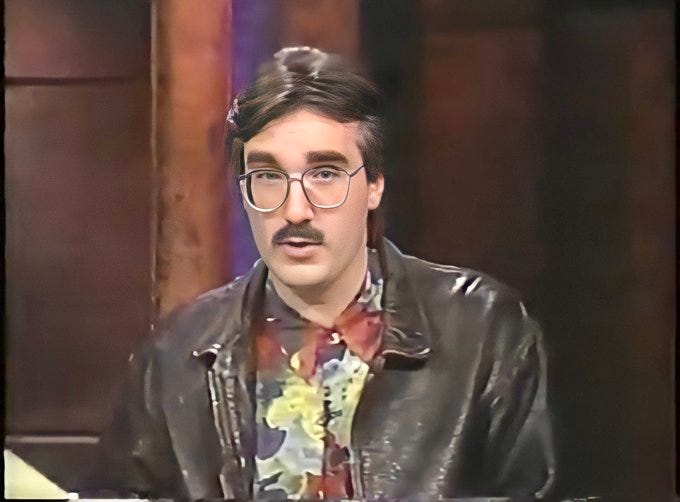

Turns out the visionary was correct. The phone was a disaster. Only 10,000 people on planet Earth bought one, over a hundred million dollars were lost, and after a year it was ended. Perhaps the most spectacular of all ESPN’s failure, and this is from the people who once put Keith Olbermann on the air looking like this:

Stories of failure are a dime a dozen, especially in tech.3 So why this one? Because flash forward 17 years and ESPN is the dominant player in sports on mobile devices, to such an extent that it is difficult to overstate. Which seems surprising. Even more surprising is that this success was directly caused by the ESPN Phone. How did a massive failure lead to so much success?

There’s endless articles about how some tech or business or creative failure led to eventual success. I once wrote about failed products that required some other innovation to make them successful. But that’s nothing like this. When discussing the future I am – to steal a phrase from one of my favorite Substacks – rarely certain. But this time I’ll say it: there is no possible future where the ESPN Phone is successful. Yes, compared to 2006 our networks are faster, our screens are bigger, and our video is crisper. But a cell phone designed for sports score is a bad idea and will never work.

The most common form of “failure leading to victory” formulation was most eloquently put by that bard of my generation, Sean Carter, when he said “But I will not lose, for even defeat there’s a valuable lesson learned so it evens up for me.”4 There’s a plethora of this content, but I am choosing this Forbes article for being wonderfully representative. You’ll notice that the reasons are related to learning a lesson, such as resilience or humility. But what lesson did ESPN need to learn? That almost no one would pay money for a phone devoted to ESPN?

This was not about waiting for new tech or learning valuable lessons. It was that in building the technology to power the ESPN phone they managed to solve all the problems and build all the tech that would power their mobile experience. The very technology originally built for the phone was used to power ESPN’s app and desktop site. Everything from streaming live games to push notifications was originally built for the phone. The entire backend of their current system was built for a doomed product. It turns out they built a good product, just one that no one wanted, and when the App Revolution began, ESPN was uniquely positioned to dominate that market.5

This is typically the point where I’d talk about the moral of the story, but I’m not sure there is one here. This may just be me writing about something I found interesting. But if there is a lesson I think it’s this: if you’re going to fail, fail towards the future.

For all the failure, ESPN correctly understood that the future of content was mobile, and tried to create the first of its kind. Contract that with ESPN’s competitors, their most fierce of which – Fox Sports – was at the same time pouring obscene money into trying to take ESPN’s throne. They were, of course, unsuccessful. Yet, as far behind as they are on television, it’s worse on mobile. Can you think of a single sports fan who uses the Fox Sports app? Yet, there was clearly an opportunity there as no one had yet won mobile. If whatever executive in charge had actually paid attention at that The Art of War for Business Leaders conference he attended, he would have attacked where his enemy was not. In this case, the future. Instead, they fought them where they were strongest, and lost. ESPN may have lost out to Apple and Google in becoming a smartphone goliath, but they destroyed their real competitors.

Not to keep going to this well, but look at Netflix. The original Netflix business model was a failure. Estimates are that Netflix only has 1.5 million subscribers for DVDs. But they built a massive customer base by offering movies through the internet as opposed to brick and mortar, and the moment broadband was able to meet their demands, they abandoned the doomed business model for the future.

A more extreme example is Instagram. The original version was a check in app called Burbn. Remember those? This was part of a gold rush into a business model that led right off a cliff. But in building Burbn, they had built funding, a team, and a nifty little photo feature that, once everything else was torn away, resulted in a product sold for a billion dollars.

What’s interesting is that the word Instagram founder Kevin Systrom uses to describe this is “pivot.” It’s also the word used to describe Netflix pivot to streaming. But these seem distinct from something like Starbucks deciding that instead of just selling beans and machines, they could pivot to selling their own espresso. A business based on a flash in the pan form of media? A mediocre version of Foursquare? That seems different, that seems like a bad idea. But because the failures were towards the future – in still unclaimed areas using emerging technologies – they don’t get called failures, they get called pivots.

There is a saying beloved both by crypto hawking celebrities, Baba Yagas, and the people we started with, the Romans: fortis fortuna adiuvat. Fortune favors the bold. Netflix saw an aging giant and decided to compete with them where they weren’t. Kevin Systrom saw the gold rush of check in apps and tried to build a better version. And ESPN saw that the future mobile. Sure, none of those ideas worked in the end. But they paved the way to victory.

As always, no one should take any (non-legal) advice from me. Ever. But if there is a lesson in the hilarity of a channel that shows sports trying to build they’re own cellphone, it’s that if you are thinking of taking a big swing towards the future, maybe you should go for it. Because even if you fail, it may be an ESPN Phone Defeat.

Tempted to turn this into an advertisement for my law practice but, word limits and all.

I try to keep the sports content here to a minimum, but if you’re a sports fan and you’re not familiar with the Winner’s Curse you have your thing to distract you from doing work for the rest of the day.

This reminded me I hadn’t mocked Segway in a while, so, footnote.

Skip this if you aren’t interested in a long tangent about turn of the century hip hop. That lyric comes from “Blueprint 2,” Jay Z’s response to Nas following “Ether,” which was his response to “Takeover.” Can we stop pretending Nas scored some amazing knockout blow with “Ether”? It’s just four and a half minutes of implying Jay Z is gay. It’s 2023, can we finally acknowledge how overrated this track is? Of course, “Takeover” was produced by Ye Who Must Not Be Named so perhaps this entire episode aged poorly.

This is where it should be noted that the ESPN App is utter trash. Perhaps the worst part of it is that it actually discourages me to watch highlights. Oh, I need to watch a 30 second Progressive commercial before I watch a 10 second highlight even though I pay you both through my cable subscriber and your streaming service? No thanks.

I love the idea that we should “fail toward the future,” which reminds me of my brilliant mother-in-law. (Really!) In the early 1980s, she put together an interactive database called Arts and Sports, which listed all the venues in the country. It was what would become normal once we had the internet, but she came up with the idea before a wide audience saw the need for it.

She also started a nonprofit that brought parents of Head Start kids to the free museums in DC, with the idea that the parents would then take their kids--her insight was that if you educate the parents, a single intervention is propagated multiple times, but if you just take the kids to the museums, it’s a one-off only. But she was so ahead of her time (this was the mid-90s) that she couldn’t get any funding. Philanthropists were used to providing direct services to kids and just didn’t get the concept of helping the parents (who were themselves in their late teens or early twenties). Now, there are programs like Harlem Children’s Zone, which help parents--and it seems so obvious to all of us that this is a good idea.

It has been interesting for me to watch the country come around to her good ideas--too late to help her projects succeed, but at least she can say she knew the right thing to do long before anyone else did!

This is an interesting story because as someone who quite often checks sports scores, game schedules, standings, and at times steals sports from my phone, the ESPN phone doesn’t sound like a recipe for the massive failure it was. But I think that’s because I’m not remembering 2005 correctly from my 2023 perspective. So it’s really that the phone was a matter of knowing what people wanted before they knew what they wanted or could understand the idea at all. Which, I suppose, is the very type of idea that can be pivoted toward the future and massively successful.