Two of the types of discourse I despise most on the internet are generational discourse and “here’s why I’m special” discourse. This, of course, means I’m going to make the following statement: my generation was pretty special.

I assure you, this is not narcissism or sublimating a burgeoning midlife crisis triggered by turning 40. Those of us known as Xennials, Geriatric Millenials, or perhaps most helpfully, Oregon Trailers, were a micro generation that is special for something entirely outside of our control. We came of age at the precise moment that the world was changing from analog to digital. We were young enough that most of us could be exposed to computers at an age that we took to them like ducks to water.1 But we’re also just old enough to remember the analog world. We remember pay phones, travel agents, and yes, even Blockbuster. Because the only people who appreciate technological advances are those there at the moment they occur, we have a very strong appreciation of, for example, Netflix, and Uber, and Airbnb, and Amazon. This gives us a unique ability to look at the technology the digital revolution has provided. And we intuitively understand how different the world we inhabit as middle-aged adults is from the world we saw our parents live in. But also, at the end of the day, so what?

A few weeks ago, CFOTS2 Klaus published a piece that asked the question: what is tech? I’ve said before that I take a much stronger – and more traditional – usage of the term than the way we use it in modern parlance. But, when people say “tech” they don’t mean the dictionary definition. So instead of being willfully obtuse I’ll try and answer this question, which has been what I’ve - in a very round about way - been doing for the last month. What is tech?

In trying to answer this question, I landed first on the answer that it is mainly just vibes. We know tech when we see it. Apple and Samsung feel like tech companies because they make computers that we carry in our pockets. Fiat and Honda don’t feel like tech companies because they make computers on wheels that carry us around. But, to paraphrase Klaus, why is a company that makes a website to sell stuff a tech company but if you sell stuff and then make a website you’re not? So is it just vibes?

I don’t think so. We typically refer to “tech” as being those things birthed by the Third Industrial Revolution, namely digitization and networked computing. This means we think of the companies we’ve discussed over the last few weeks as “tech” and we don’t think of companies like Walmart, Yellow Cabs, or Hilton as “tech,” no matter how much of that technology they actually use. These “tech” companies are native to that digital world, while legacy companies just add the technology in.

Of course, as we’ve spent the last few weeks discussing, this is nonsense. Most of these tech companies aren’t doing anything native to digitization or networked computing, they’re just using these elements to slightly improve pre-existing processes. Which leads into the far more worrisome question: what’s the point of these tech companies?

If I’m of the exact age where I can distinguish what I do from what I could’ve done if this was 1992, let’s ask what is really different. This morning I woke up and my alarm clock read me the news and weather. This is, I suppose, slightly better than if my alarm clock had just been set to the news station. Then I used my iPad to read news, which saved me having to subscribe to a newspaper and also allowed me a wider range of sources than I would otherwise have had access to. I then “went” to work, which was done from my home. I could do this because what would’ve been paper files are now all digitized and I can access them from anywhere. I was able to email people which is preferable to constant phone calls or the slowness of regular mail. At various points throughout the day I texted friends – which allows for communications that otherwise would not have occurred. Similarly, I conversed with people on the internet who I would not know otherwise. I ordered dinner through Doordash3 which saved me the benefit of having the menu or having to call the restaurant or give them my credit card information over the phone. When I came back upstairs I opened my door with a fob, not a key. I watched last night’s episode of What We Do in the Shadows without having to set my VCR. I was able to join friends I am geographically distant with to dominate strangers at NBA2k22. And I put these words onto the internet, to what is – theoretically – a larger group of people who would otherwise read them. Theoretically. Seriously, like, subscribe, and share people.

I’m not going to pretend like that isn’t a more enjoyable life than I would’ve had in 1992. As this day in the life shows, there’s been real improvement in our ability to communicate with each other. But the difference isn’t exactly fundamental. My life hasn’t been disrupted. Most of the real change – and I would argue improvement – come from technologies over a century old. The telephone, the automobile, and most importantly here in Texas, the air conditioner. My life without those things would be hellish. My life without some extra television options and Twitter would be slightly less fun. Some may persuasively argue it would be better. That’s not to say these haven’t had huge effects. Obviously, a lot of these technologies have helped make a lot of workers redundant and increase profits. But for humanity as a whole, even as I sit here typing on a laptop, I have to ask, is this it?

Granted, small improvements are good. As I once wrote, they’re quite underrated. But as anyone else my age can tell you, the internet was billed as a much bigger deal than this. The Digital Revolution was going to change the world. And this has not felt societally changing. This has felt like something that has largely produced skeuomorphic applications. We take things from the real world and replace whatever can be digitally replaced. The first big use to the public of the internet was electronic mail which, the name gives that away. Even all the buzz around Web 3 – at least prior to the crypto crash – was essentially skeuomorphic. Cryptocurrency and NFTs are – and this pun is most definitely intended – mainly aping the world we already know.

If I could witness any moment in humanity’s long journey I would choose the first time a human ate something cooked with fire. Not because it was the most important, but because of the most important moments it had to be the most hilarious. It didn’t change how humans ate on the most fundamental level. We were still taking things from a small subset of other species and putting them in our mouth. But the quality was so much greater its knock-on effects literally changed our brains. We improved something to such a degree it practically created humanity.

Of course, fire didn’t just give us that. It also allowed us to do genuinely new things, such as clear land, move into cold climates, start adopting shelter, etc. Now, the distinction between an improvement that creates a fundamental change and a genuinely new thing is probably best left to philosophers. But I feel that to a degree, we can tell it when we see it. Was being able to hail a taxi from people without taxi licenses an improvement? Probably. Was it a fundamental change? I doubt it. Was it a genuinely new thing? Absolutely not. Conversely, would living on a different planet be an entirely new thing? I’d say so. Would uploading our disembodied consciousnesses into computers that are linked so we all share one unified existence? I’m comfortable saying yes, that would be a big deal. Think about the changes wrought by the Agricultural Revolution. Or the First Industrial Revolution. We’ve briefly touched on how much of the most important technology of today is rooted in the Second Industrial Revolution. People call this the information age but has the invention of the internet even had the same type of impact as the invention of writing or the printing press? Perhaps if you’re really, really into kitten videos or pornography. But otherwise, this doesn’t seem on that level.

Yet, this all makes perfect sense and isn’t even particularly surprising. First, as this series has shown, there’s nothing entirely wrong with not being able to create a fundamentally new thing. We’ve been on this planet for more than a little while. We’ve worked out a lot of things that are good. Improving them with digital technologies – or the massively improved communications that allowed us to build – has a lot of utility. Not everything needs to be fundamentally changed. Afterall, the printing press didn’t fundamentally change how we consume information, it just made information more prolific. The real change was the invention of writing. That fundamentally changed how humans live, it’s why we call it history. The printing press was essentially a phase shift, and a big one. And it’s not ridiculous to think the internet could still reach that level, which is the second reason this all makes sense.

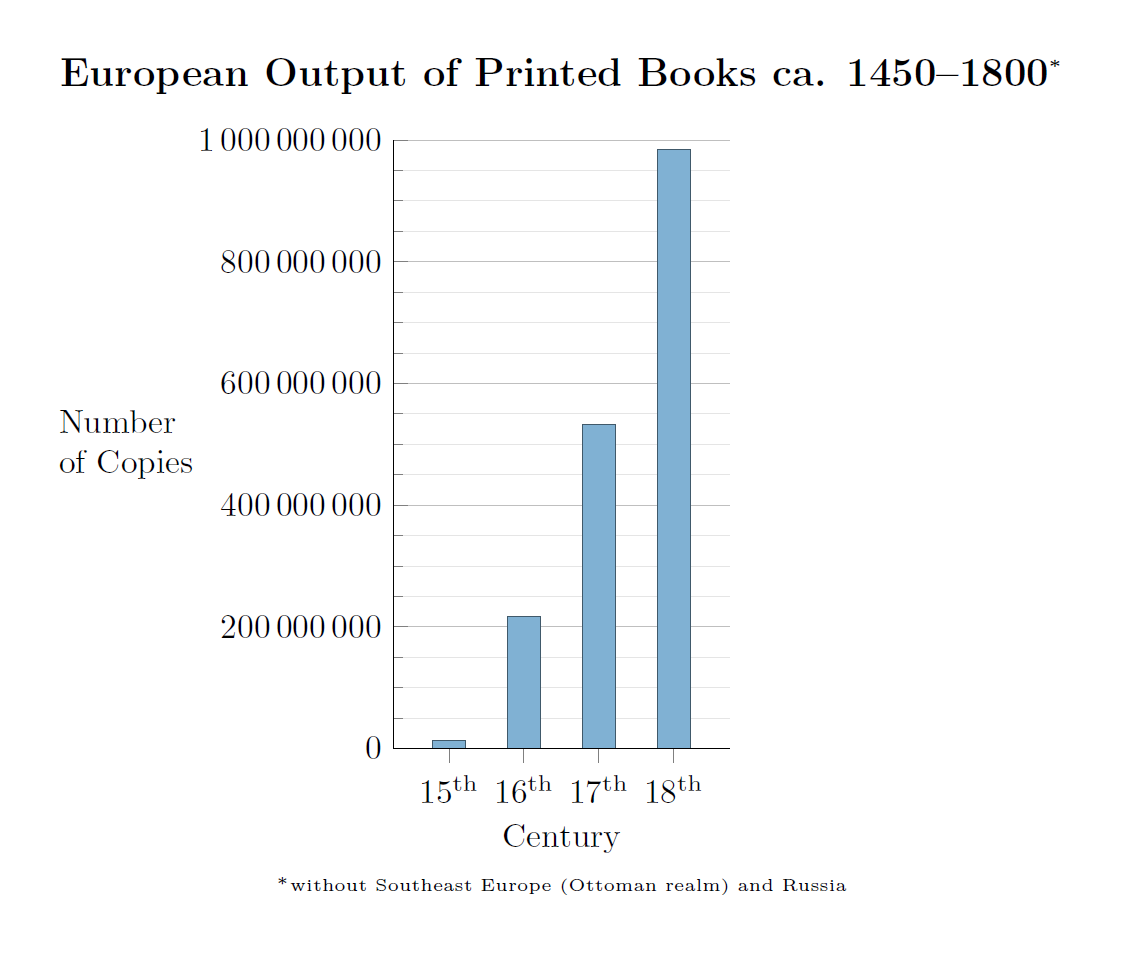

This is all still incredibly new. Even accounting for the lack of a Renaissance Moore’s Law, think about how the Gutenberg Bible was printed thirty years before Martin Luther was born. Or, enjoy this handy chart I stole from Wikipedia about the rate of book printing in Europe by century:

Everything that we’re discussing has to be done with the realization that these are still early stages. The harsh truth is that we’ll all be dead long before anything approaching the full power of this new thing is even close to being realized.4 We’re judging a technology in its infancy. Is it any surprise that we’re seeing slightly improved versions of what we already have?

At the end, I hope this series has shown that a lot of this “disruption” and “revolution” is somewhat overblown. But it’s also not true that this is all we can do. If we focus only on using these impressive technologies to make watching sports slightly better and dating slightly worse, we’re not going to come close to tapping into this for a long time. And unfortunately, we’re using the best and brightest to slightly improve our ability to target advertising. What we need to do is start thinking bigger. We need to start thinking about how we can use these new technologies and create new ways of using them, which is the opposite of how we think about these things. What is the digital version of using fire to cook food? We may not know the answer to that for a long time. But it’s better to ask that question repeatedly without getting an answer than to ask how we could create slightly better fitness classes. Which means the answer to “what is tech” is “we really don’t even know, yet.”

I cannot detail all the times that I have had lawyers who are only slightly older than me become befuddled at Excel or Google Docs, which to me are as natural as breathing. I’m sure everyone else my age has similar experiences. Like all generational discourse, it is important to note that there are countless people significantly older than me who are better with technology than I am. But broadly, this statement is true.

Certified Friend of the Stack

Y’all see how easy it is for me to work advertisement in here? Shoot me an email, companies with money.

When I do sublimated midlife crisis, I do it existentially.

This is good, but I have to push back a bit on your "perfect age" statement. I'm older - geriatric Gen X?! - and I think much of this applies to my cohort and everyone in between. Personally, I hate food delivery and Uber (I'm a transit nerd), so maybe I don't "appreciate" the changes as much. That said, though, I notice and am grateful for many of them every day. I do remember "long distance" phone calls, very expensive flights (and more frequent crashes), and, as an enthusiastic correspondent with far-flung friends, the vagaries of snail mail.

Re fn 1, I would argue that lawyers are perhaps uniquely terrible with technology. I am a lawyer, but don't practice. My husband (similar age to me) is part of a law firm, and can barely use his gmail or Office suite. His colleagues, and my law school friends who have remained immersed in Law World, are the same, even younger ones. I'm sure the Very Youngs new to the firm are better, but the tech unsavviness goes deeper than one would expect. I think part of the reason is that, at least in private practice, there is still so much support staff, and attorneys are unaccustomed, or unwilling, to do things perceived as menial for themselves.

Really enjoying this series!

We need better avenues for smart people. A lot of people want to work on something useful, but end up accepting jobs at "tech" companies of questionable value because that's where the jobs are.

I also think the lack of a clear existential threat hurts innovation. Climate change isn't gonna do it, so there's no grand incentive to improve things in a major way.